By Adam Pagnucco.

It’s election season and that means it’s time for lots of promises from politicians. And boy are they promising a lot, especially on the county’s two big issues of education and transportation. The mailbox’s “progressive leaders” have “plans” to guarantee every child a great school, invest in transportation – especially transit – and to do all of the above without raising taxes. Sounds great, yeah?

Time to get real, folks!

Education and transportation each have two virtues. First, each of them generates direct economic returns. Education spending yields a return on human capital while transportation spending yields a return on physical infrastructure. Both are important for attracting and retaining residents and jobs. Second, each of them is popular with voters. For as long as anyone can remember, education and transportation have been two of the top issues in our elections – and they might possibly be THE top two. Happily, on these two issues, good policy and good politics come together!

Paying for them is another matter. MCPS accounts for a greater percentage of the budget than any other agency with a $2.5 billion budget in FY18. Montgomery College received more than $300 million. The Department of Transportation’s operating budget was $56 million. Funding increases with meaningful impacts on these agencies need to be in the tens of millions of dollars – at least. That kind of money far exceeds a spreadsheet rounding error.

And yet, there is a way to increase spending on MCPS, the college and transportation without massive tax hikes. The catch is that it’s not quick or easy.

Let’s do a simple (and yes, admittedly simplistic!) exercise with the operating budget. First, let’s identify the combined local dollar spending on MCPS, the college and the Department of Transportation (DOT). Next, let’s segregate out intergovernmental aid, which plays an important role in the budget but is not controlled by the county government. Then let’s segregate debt service. Yes, over long periods of time, the county can adjust debt service. But much of the debt service is being paid on capital projects already completed, and furthermore, a huge chunk of it goes to school construction and transportation projects. Boosting education and transportation operating budgets by cutting their capital budgets is not the best idea in the world! Finally, let’s subtract out local dollar education and transportation spending, intergovernmental aid and debt service from total spending and what we get is a great big category that we shall creatively name “Everything Else.”

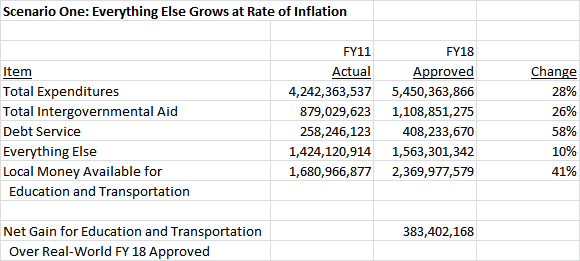

Here’s what happens when we do that for FY11, the trough budget year of the Great Recession, and FY18, the budget that ends on June 30 of this year.

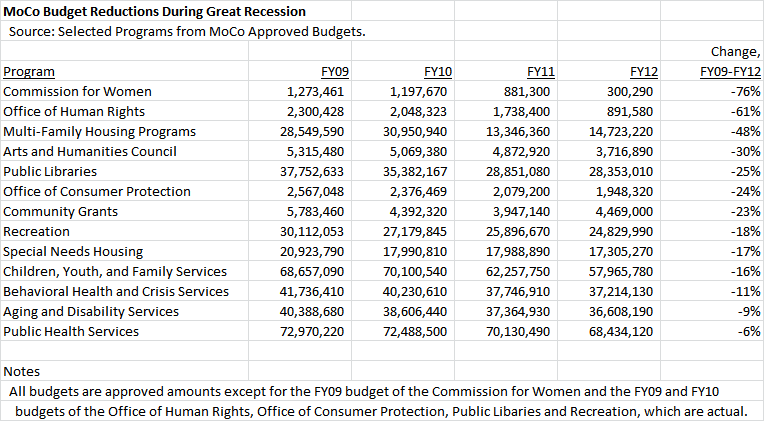

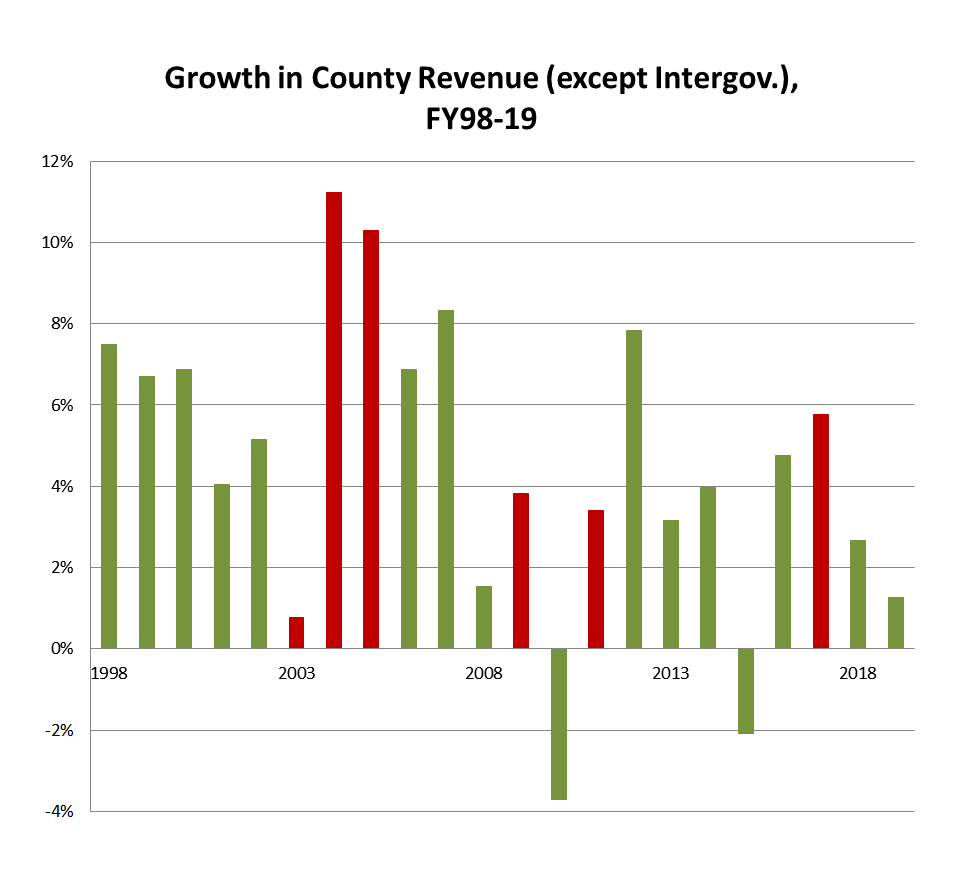

What the above data shows is that the total county budget grew by 28% over this period. Intergovernmental aid grew by 26% and debt service rose by a whopping 58%. (We have previously written about the county’s rapidly growing debt.) Now let’s contrast the two remaining broad categories: the local dollars spent on MCPS, the college and DOT and everything else. The education and transportation budgets grew by a combined 18%. Everything else grew by 37%.

That’s right folks – spending on everything else has been growing twice as fast as local dollar spending on education and transportation operating budgets. That’s a strange fact in a county in which education and transportation are arguably the top two political issues.

Now what would have happened if the everything else side of the budget was restrained to grow at the same rate as inflation? The average annual growth rate of the Washington-Baltimore CPI-U since 2011 has been 1.3%, meaning that prices have grown by 9.8% over that period. When we hold the total budget, intergovernmental aid and debt service constant and assign a growth rate of 9.8% to the everything else category, here’s what happens to local dollars available for education and transportation. For the purposes of discussion, let’s call this Scenario 1.

In Scenario 1, $2.4 billion is available for education and transportation because of spending restraint on everything else. That’s $383 million more than the $2 billion that was actually available in the real world FY18 budget.

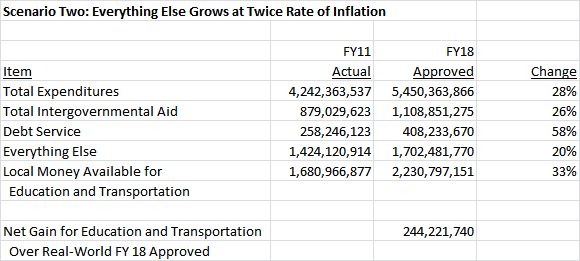

Holding a big chunk of county government to the rate of inflation for seven straight years is tough medicine and very unlikely. So let’s create a Scenario 2 in which the everything else category is restrained to twice the rate of inflation, or 19.5% growth since FY11.

In Scenario 2, $2.2 billion is available for education and transportation, $244 million more than the real world FY18 budget.

For the sake of comparison to both of these scenarios, let’s recall that the 9 percent property tax hike was supposed to raise $140 million a year. (It probably raised a little less than that.) So under both scenarios, the county could have avoided the giant tax hike and still had lots of money left over for more education and transportation spending.

Yes folks, we understand the radical nature of what we are proposing – namely that liberal Democrats should deliberately and strategically restrain the growth in some forms of spending to boost growth in other spending. This is likely to be an unpopular concept in a county that has multiple jam-packed budget hearings every year with groups of all kinds requesting money. But here’s the benefit to concentrating on education and transportation: both forms of spending are investments that generate returns for the economy. And when those returns boost economic growth, they generate tax revenue that bolsters the entire budget.

What is necessary to pull this off? Simply put, this requires strategy, discipline, patience and leadership. Without those traits, given the huge number of constituencies that want their piece of the budget, it would be impossible to focus it on education and transportation. The natural outcome of a budget process without strategy is that everything gets funded, a tax hike follows, voters tire of it and then they pass restrictive charter amendments and vote for politicians like Larry Hogan.

So what are we going to get? Spending on everything followed by tax hikes? Or a budget that is strategically focused on generating economic returns from education and transportation?

Folks, that depends on your decisions in the voting booth.