By Adam Pagnucco.

As we stated in Part One, we have examined nearly 9,000 records of contributions to thirteen countywide candidates in the public financing system who have qualified for matching funds: County Executive candidates Marc Elrich, Rose Krasnow and George Leventhal and Council At-Large candidates Gabe Albornoz, Bill Conway, Hoan Dang, Evan Glass, Seth Grimes, Will Jawando, Danielle Meitiv, Hans Riemer, Mohammad Siddique and Chris Wilhelm. Today we begin to answer the question of where individual contributions in the public financing system are coming from.

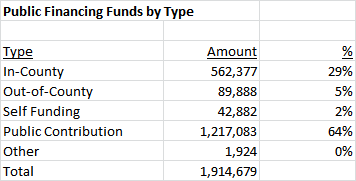

First, let’s tally the aggregate sums collected by all thirteen candidates.

The largest source of money in the public system is public matching funds, which outnumbers private contributions by more than two to one. But that understates the magnitude of matching funds because the contribution records do not include public funds requested but not yet disbursed. We will examine that issue when we begin discussing individual candidates in Part Three. One note: while candidates may not take corporate contributions, their accounts may accept vendor refunds, deposit returns and bank interest. That accounts for the tiny amount in the “other” category.

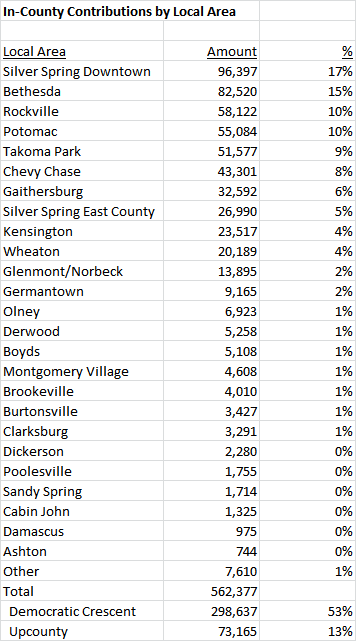

Now let’s look at in-county contributions by local area.

Urban centers that are also Democratic strongholds tend to dominate here, especially Downtown Silver Spring and Bethesda. We have previously identified an area we call “the Democratic Crescent” including Takoma Park, Downtown Silver Spring, Kensington, Chevy Chase, Bethesda and Cabin John that accounts for 23% of the county’s population, 29% of its registered Democrats and 37% of its Super Democrats (those who voted in each of the last three mid-term primaries). That area accounts for 53% of in-county contributions in the public financing system.

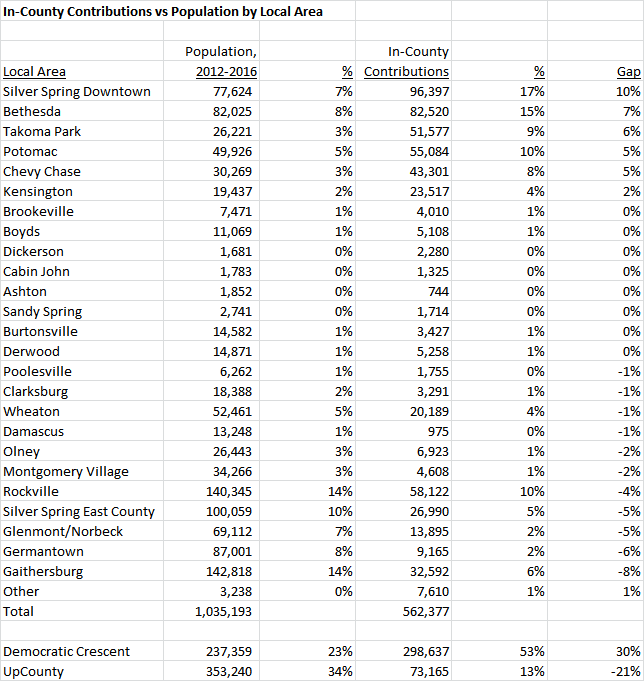

Below we compare in-county contributions to population by local area.

Relative to their population, Downtown Silver Spring, Bethesda, Takoma Park, Potomac and Chevy Chase are over-represented in terms of in-county contributions. Gaithersburg, Germantown, Glenmont-Norbeck (zip code 20906) and Silver Spring East County (zip codes 20903, 20904 and 20905) are under-represented. The Democratic Crescent accounts for 23% of the county’s population but 53% of in-county contributions. Upcounty, an area we define as including Ashton, Boyds, Brookeville, Clarksburg, Damascus, Dickerson, Gaithersburg, Germantown, Montgomery Village, Olney, Poolesville and Sandy Spring, accounts for 34% of the county’s population but just 13% of in-county contributions.

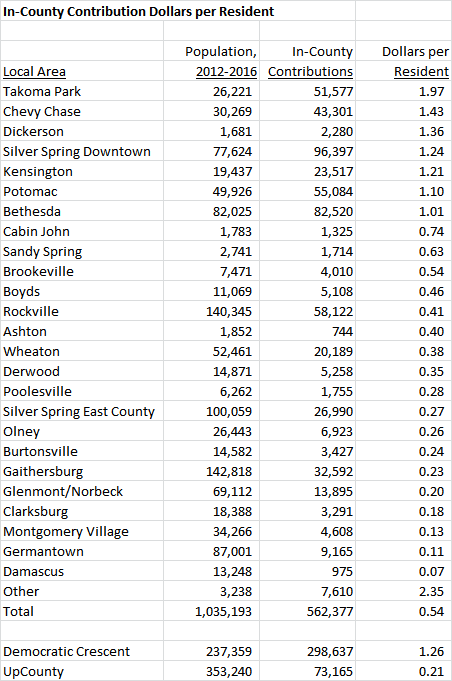

Here’s another way to look at the same data: in-county contribution dollars per resident.

Seven communities contributed one dollar or more per resident to publicly financed candidates: Takoma Park, Chevy Chase, Dickerson, Downtown Silver Spring, Kensington, Potomac and Bethesda. Except for Dickerson and Potomac, all of these areas are in the Democratic Crescent. Seven communities contributed less than 25 cents per resident: Burtonsville, Gaithersburg, Glenmont-Norbeck, Clarksburg, Montgomery Village, Germantown and Damascus. The average contribution per resident in the Democratic Crescent was $1.26. In Upcounty, it was 21 cents.

Finally, we compare in-county contributions to the distribution of Super Democrats.

The distribution of in-county contributions is a much closer match for Super Democrats than for the broader population. But Super Dem-intensive areas are even more influential among contributors. The Democratic Crescent accounts for 37% of Super Dems and 53% of in-county contributions. Upcounty accounts for 20% of Super Dems and 13% of in-county contributions. Downtown Silver Spring and Takoma Park are over-represented here even when factoring in how many Super Dems they have, while Glenmont-Norbeck, Silver Spring East County and Rockville are under-represented.

The bottom line is that public financing is amplifying the influence of heavily Democratic Downcounty areas above and beyond patterns of residency and voting. That influence comes at the expense of Upcounty areas like Gaithersburg, Germantown, Clarksburg, Damascus and the smaller communities close to the Frederick and Howard County borders. If corporate money and PAC money are thought to have outsize impacts on the actions of county government in the traditional system, then one wonders if the Downcounty dominance that some Upcounty residents complain about will be even more pronounced due to public financing.

In Part Three, we will begin examining specific candidates.