By Adam Pagnucco.

Today, we conclude looking at jurisdictions with whom MoCo has had inflows and outflows of tax returns and adjusted gross incomes.

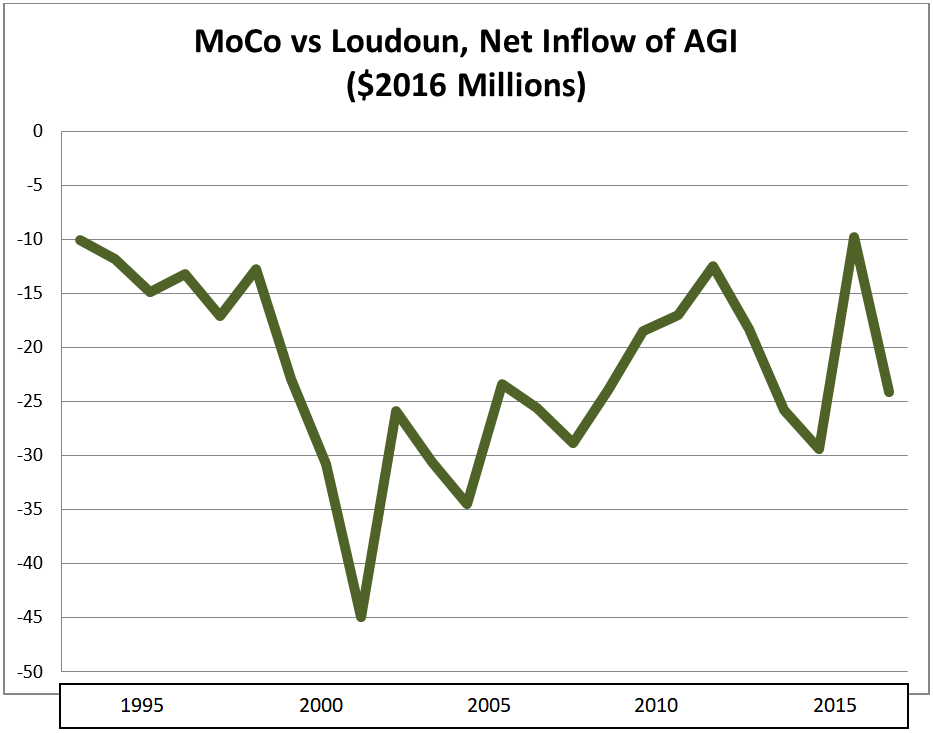

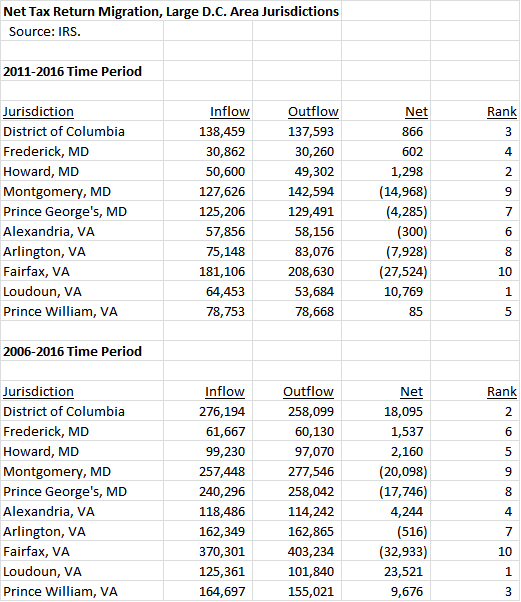

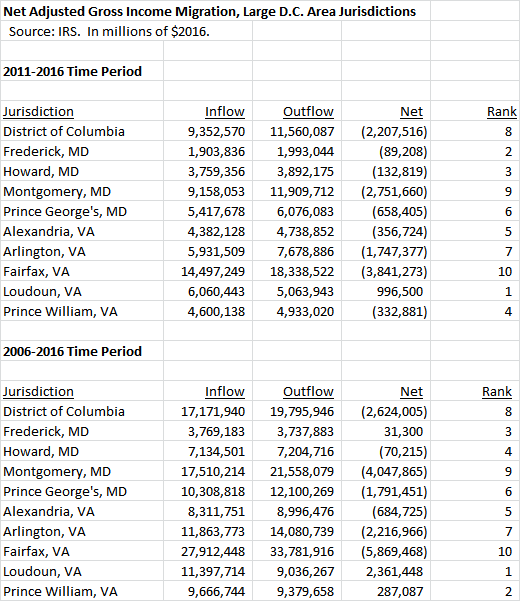

Loudoun County

Net change in tax returns, 2006-2016: -1,507 (outflow)

Net change in adjusted gross income ($2016), 2006-2016: -$208 million (outflow)

Adjusted gross income of in-migrants ($2016), 2006-2016: $76,287

Adjusted gross income of out-migrants ($2016), 2006-2016: $100,587

Migrant income gap: Out-migrants earned 32% more than in-migrants

Loudoun has been the fastest-growing large jurisdiction in the Washington region for a long time and was once one of the fastest-growing places in the country. Much of its growth has come from people relocating from Fairfax but it has gained some folks from MoCo too. As the wealthiest county in the nation, it’s no surprise that its migrants from MoCo skew to high earners.

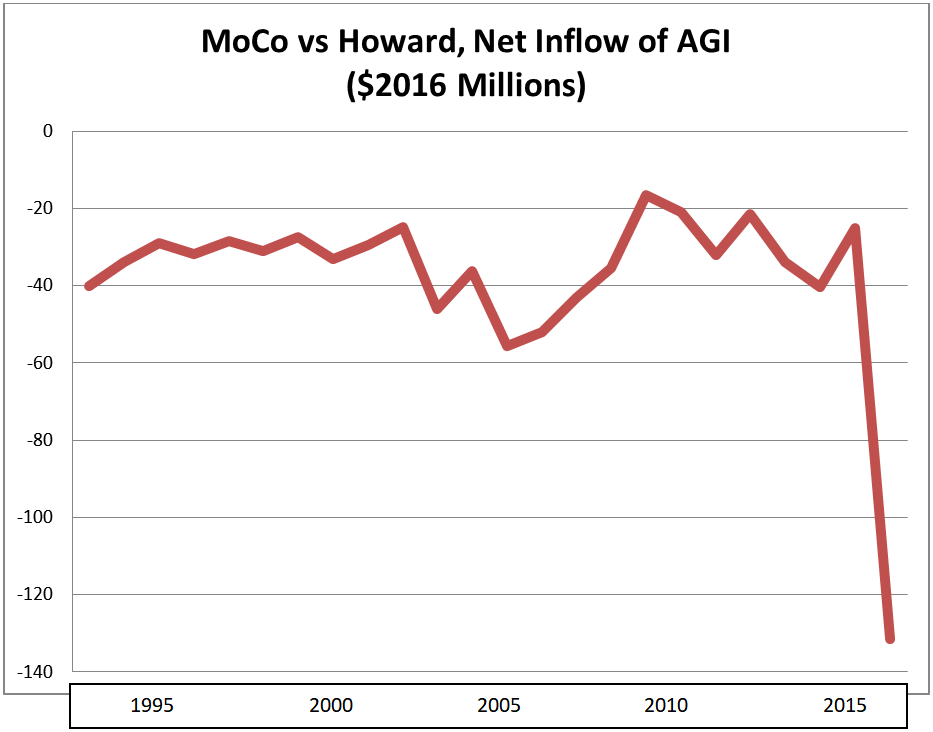

Howard County

Net change in tax returns, 2006-2016: -2,859 (outflow)

Net change in adjusted gross income ($2016), 2006-2016: -$400 million (outflow)

Adjusted gross income of in-migrants ($2016), 2006-2016: $72,231

Adjusted gross income of out-migrants ($2016), 2006-2016: $90,724

Migrant income gap: Out-migrants earned 26% more than in-migrants

Howard is MoCo’s smaller and wealthier neighbor to the northeast. It gains relatively small amounts from MoCo every year but set a record in 2016, when $131 million of taxpayer income left MoCo for Howard. Howard’s schools and quality of life are comparable to MoCo but its significant distance from D.C. has limited its ability to compete for people who work downtown. Ironically, the joint bus rapid transit route on US-29 that MoCo is working on with Howard could help remedy that disadvantage.

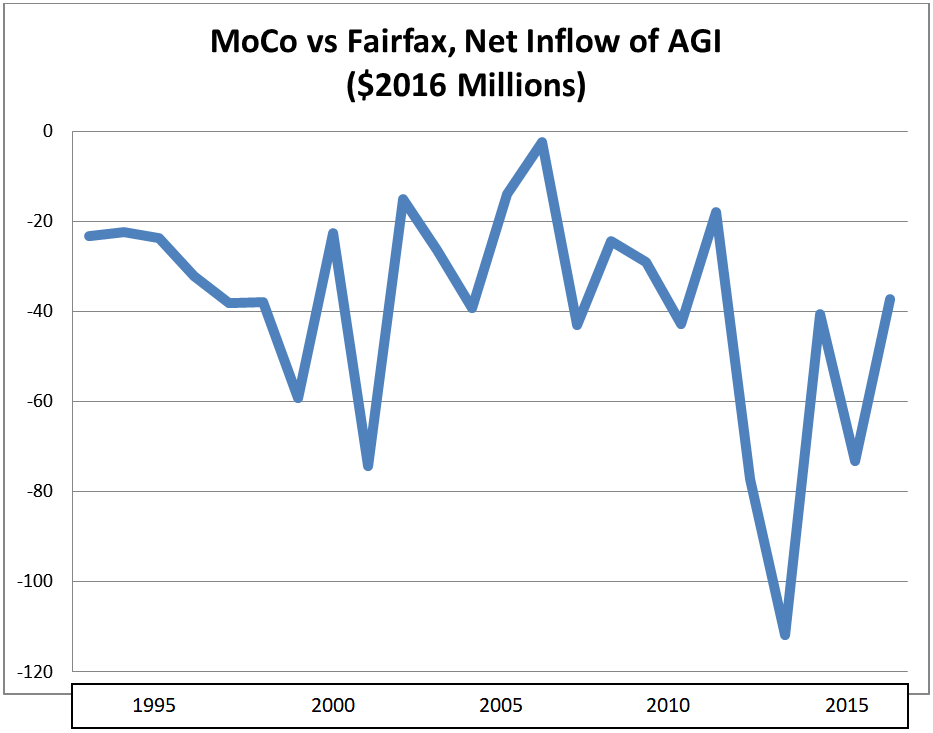

Fairfax County

Net change in tax returns, 2006-2016: -2,382 (outflow)

Net change in adjusted gross income ($2016), 2006-2016: -$497 million (outflow)

Adjusted gross income of in-migrants ($2016), 2006-2016: $70,796

Adjusted gross income of out-migrants ($2016), 2006-2016: $93,521

Migrant income gap: Out-migrants earned 32% more than in-migrants

Fairfax has had more taxpayer flight than MoCo overall and is losing a ton of income to Loudoun ($2.5 billion over the last decade). But in head-to-head competition, Fairfax siphons millions in taxpayer income from MoCo every year, setting a record in 2013 with a net gain of $112 million. A big reason for Fairfax’s gains is that the people who move from MoCo to Fairfax made 32% more money than those who moved in the opposite direction over the last decade.

Frederick County

Net change in tax returns, 2006-2016: -7,170 (outflow)

Net change in adjusted gross income ($2016), 2006-2016: -$582 million (outflow)

Adjusted gross income of in-migrants ($2016), 2006-2016: $59,150

Adjusted gross income of out-migrants ($2016), 2006-2016: $69,017

Migrant income gap: Out-migrants earned 17% more than in-migrants

MoCo’s smaller neighbor to the north has been feeding off the county for years. Frederick’s biggest gains from MoCo occurred from 2002 through 2007 during the latter’s housing price boom. Frederick is not siphoning off anywhere near the amount of income that Loudoun is getting from Fairfax, but the inflow of people from MoCo has helped change its county seat’s downtown, its demographics and its politics.

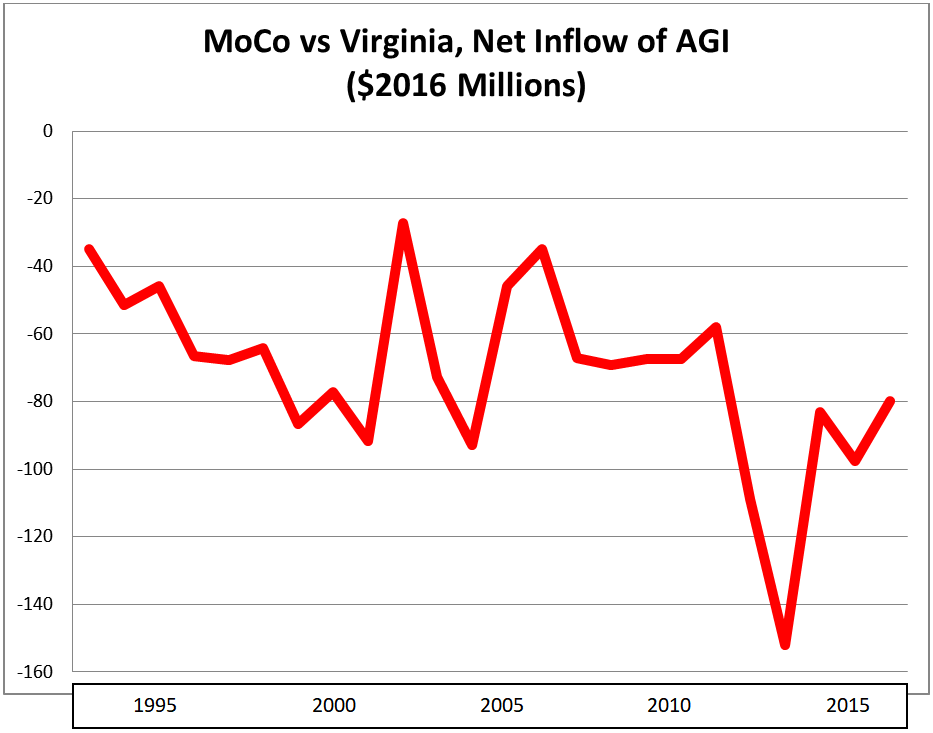

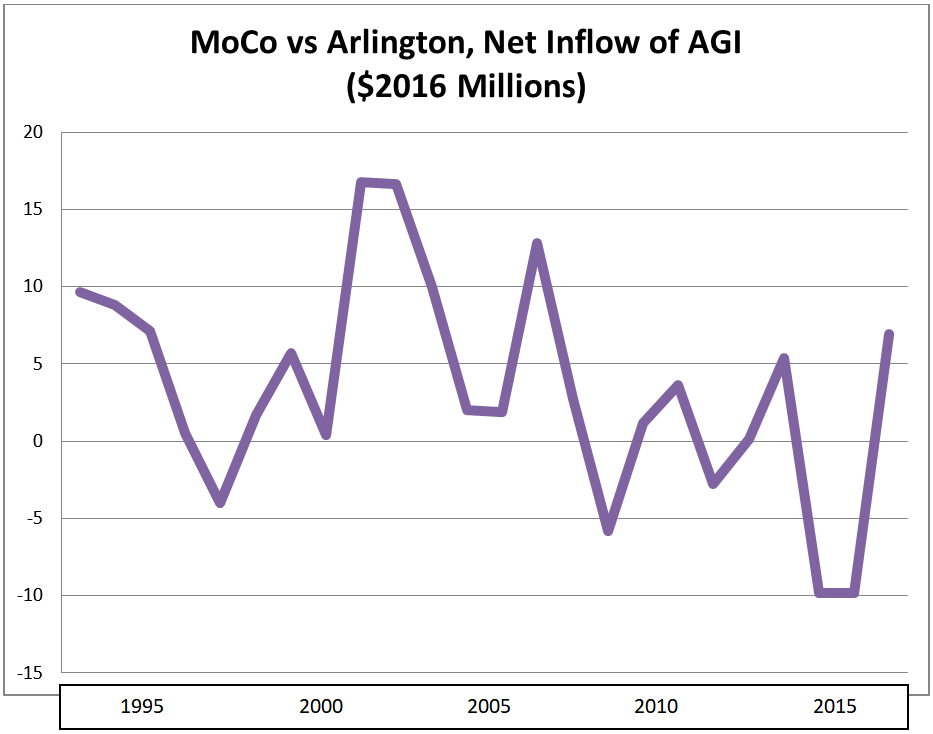

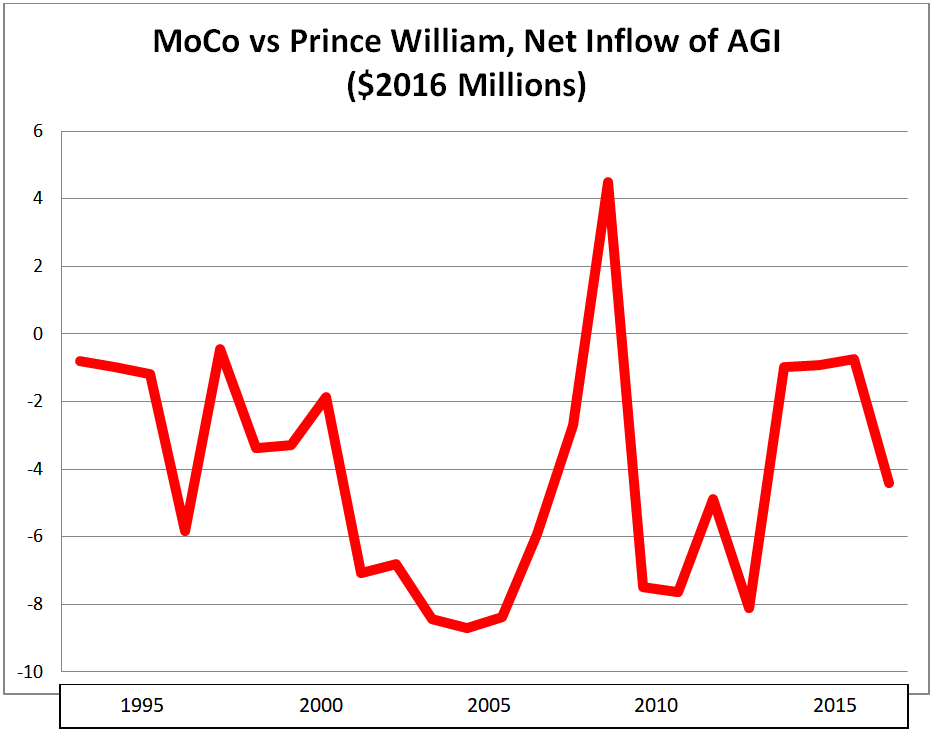

Virginia

Net change in tax returns, 2006-2016: -5,638 (outflow)

Net change in adjusted gross income ($2016), 2006-2016: -$851 million (outflow)

Adjusted gross income of in-migrants ($2016), 2006-2016: $70,701

Adjusted gross income of out-migrants ($2016), 2006-2016: $83,010

Migrant income gap: Out-migrants earned 17% more than in-migrants

MoCo has lost significant amounts to Virginia over the years, with the biggest income losses occurring in 2013 ($152 million) and 2012 ($109 million). Fairfax is the biggest culprit, followed by Loudoun and the rest of Northern Virginia. The pace of income lost has picked up considerably since the early 1990s.

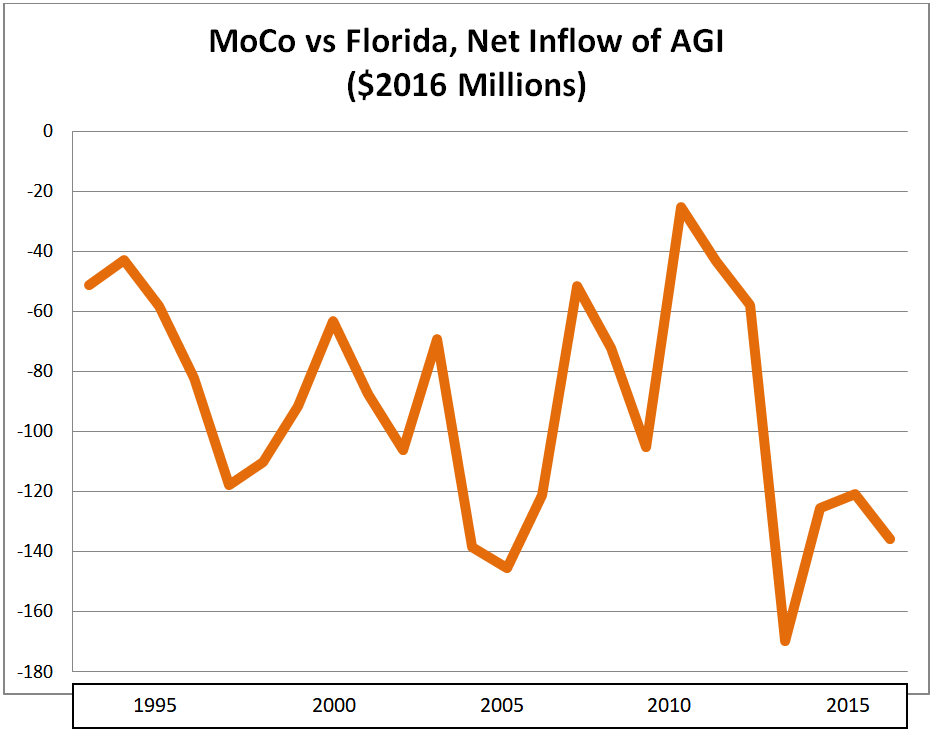

Florida

Net change in tax returns, 2006-2016: -2,769 (outflow)

Net change in adjusted gross income ($2016), 2006-2016: -$907 million (outflow)

Adjusted gross income of in-migrants ($2016), 2006-2016: $70,112

Adjusted gross income of out-migrants ($2016), 2006-2016: $132,459

Migrant income gap: Out-migrants earned 89% more than in-migrants

Everyone has heard the stories of rich people and/or retirees moving from MoCo to Florida. Well, those stories might be true: more MoCo income has been lost to Florida than to Virginia over the last decade. The number of people moving to Florida is less than those moving to Virginia. But the average income of those moving from MoCo to Florida – $132,459 – is large in both absolute terms and when compared to those moving in reverse ($70,112). One more thing: the last four years saw the biggest net loss of taxpayer income to Florida ($552 million) of any four-year period on record.