By Adam Pagnucco.

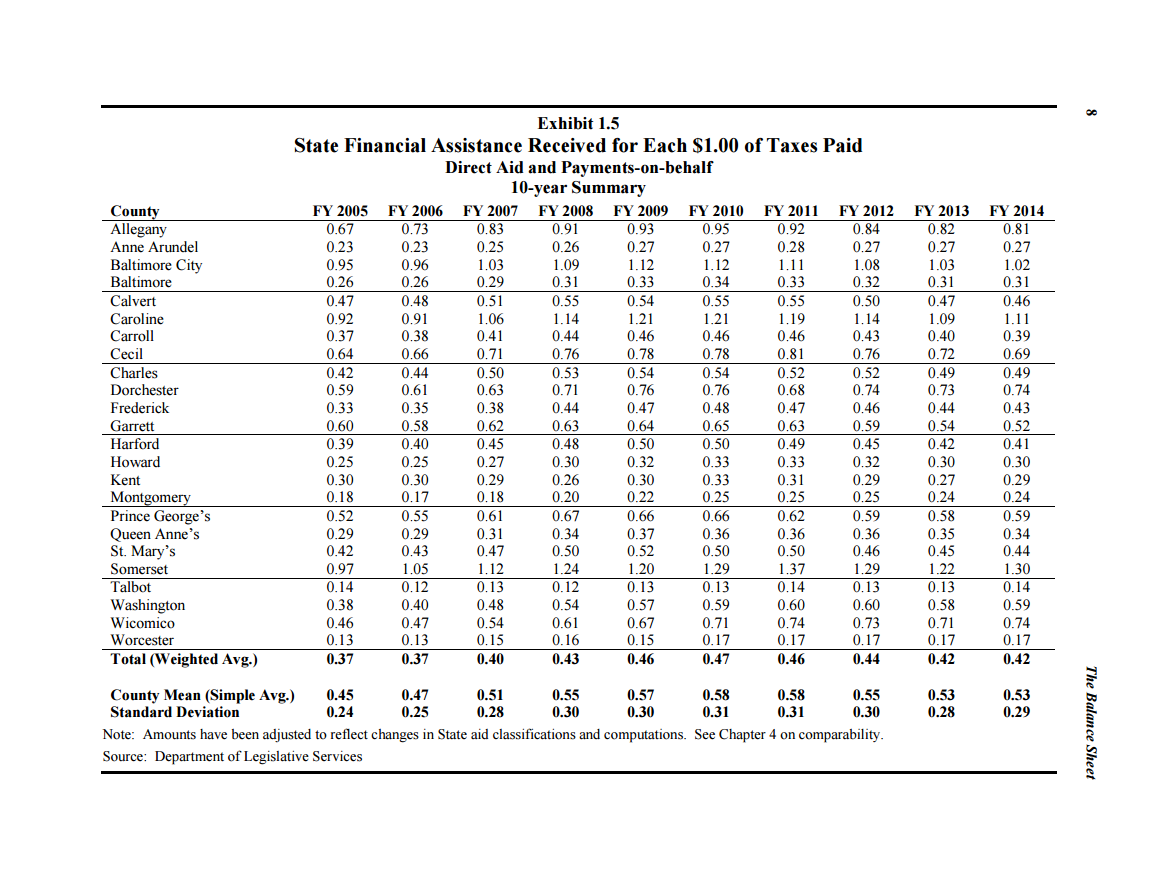

For a long time, Montgomery County has been thought of as a wealthy jurisdiction. It has long appeared in lists of the nation’s richest counties (although it is about to drop out of the top twenty). Politicians elsewhere in Maryland view it as a gold mine, with Senate President Mike Miller famously saying, “It’s like Never Neverland for other legislators of the state.” The county is regularly shorted by state wealth formulas which disproportionately distribute state aid, especially for public schools, to other parts of Maryland.

But most of Montgomery County is not particularly rich. Its wealth is concentrated in seven zip codes which skew its mean household income upward and make the county as a whole appear richer than it really is.

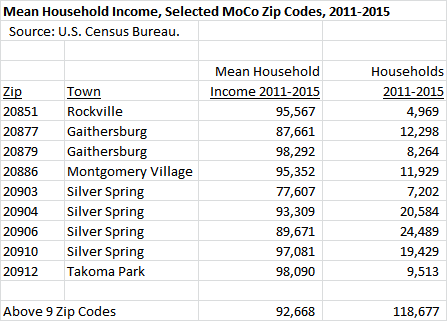

All residents of MoCo understand that there are huge differences between areas in the county even though many outsiders do not. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county’s mean household income was $133,543 over the 2011-2015 period, just barely squeaking past Howard County ($132,751) for tops in the state. But that conceals big variations. MoCo has nine zip codes in which mean household incomes were under $100,000. The combined mean household income of these areas ($92,668) is roughly equal to the mean household income of Prince George’s County ($90,268).

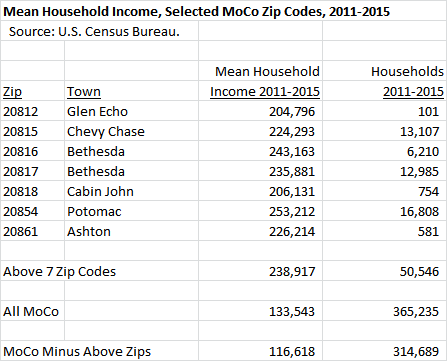

MoCo has seven zip codes in which mean household incomes were over $200,000 in the 2011-2015 period. These zip codes, mostly located northwest of D.C., account for 14% of the county’s households and 25% of its household income. If these zip codes were regarded as a separate jurisdiction, their combined mean household income would be $238,917. The combined mean household income of the rest of Montgomery County is $116,618 – about half the income of the Mighty Seven.

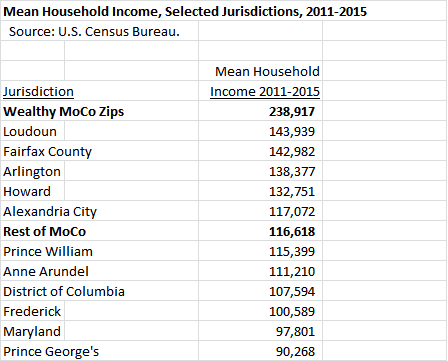

How do the mean incomes of the Mighty Seven and the rest of the county compare to the rest of the region? We show the mean household incomes of those two parts of the county along with the other large jurisdictions in the region below. The Mighty Seven as a group are easily at the top although we suspect that extracts of the wealthiest parts of Loudoun, Fairfax, Howard and D.C. would also be in that range. As for the rest of the county, its income is average compared to the rest of the region.

That’s right, folks – with the exception of its wealthiest zip codes, MoCo is a middle-income jurisdiction by the (admittedly high) standards of the Washington region.

This reality has interesting implications for policy makers and candidates. The issue of equity between different parts of Montgomery County is getting traction as a political issue in the upcoming election. But in terms of who pays the county government’s bills, there is no question that county revenues are hugely dependent on a limited number of wealthy neighborhoods, especially in the absence of robust economic growth. If those residents decide that they can get a better deal by living somewhere else, that would be a huge threat to the county’s tax base.

As for the state level, there’s a tendency to look at differing incomes and wealth BETWEEN counties but not INSIDE counties. That’s how state wealth formulas work – they compare counties to each other but not local areas to each other. How many state policy makers have understood prior to reading this blog post that there is a large part of Montgomery County that is economically comparable to Prince George’s? It’s time for a serious examination of how to direct state aid to local areas in need regardless of which county borders they happen to occupy.