Yesterday, I reviewed political science research revealing that women who run for Congress do just as well as men and, contrary to public perception, do not face hostile press coverage that harps on their gender and appearance.

So why are there substantially fewer women than men in public office?

Today and in the next post, I focus on two key factors: First, women are less likely to run for public office than men. Second, the type of office greatly shapes who runs and wins.

My discussion today relies heavily on research by Jennifer Lawless and Richard Fox, particularly their articles in the American Journal of Political Science and American Political Science Review. The APSR is widely viewed as the top journal in political science and the AJPS is one of the top three venues to publish work in American politics.

Fewer Women Run

Lawless and Fox’s Citizen Political Ambition Study surveyed 3,765 people (1,969 men and 1,796 women) they considered highly eligible to run for office, largely people in the professions of law, business and education.

Among this group of potential candidates, 59% of men but just 43% of women said that they considered running for office. The probability that those who considered running actually sought office also revealed gender differences with 20% of men but only 15% of women taking the plunge to enter the political arena.

Interestingly, among those who did run, 63% of the women held public office as opposed to 59% of men. Unlike the gender differences mentioned in the previous paragraph, this one is not statistically significant. If we want more women in public office, we need to focus on the barriers that deter women from running.

Barriers to Women Running for Office

Fox and Lawless find that women are less likely than men to discuss the possibility of running for office with family and friends (22% of women v. 33% of men), community leaders (9% v. 15%), and party leaders (6% v. 12%) than their male counterparts. Improved outreach seems a straightforward way to overcome this barrier.

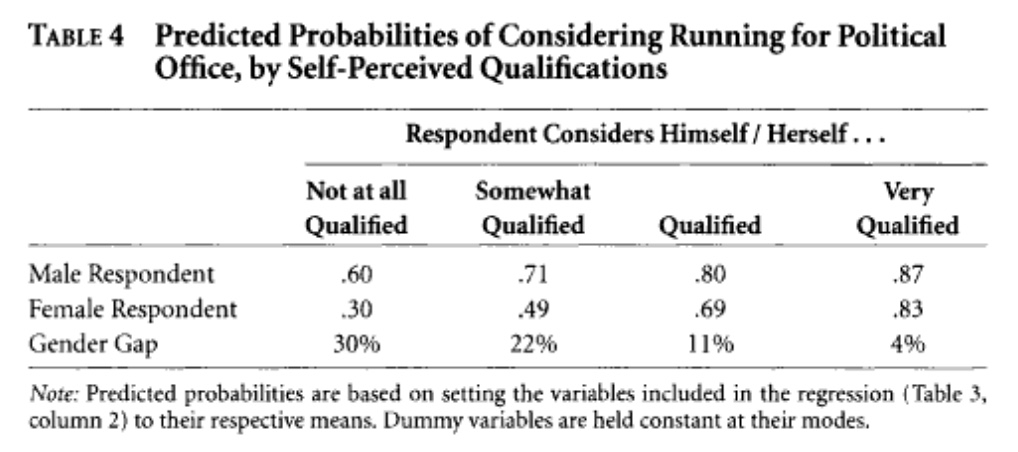

Next, Fox and Lawless showed that men are more likely than women to consider running for office even when they have similar perceptions of their qualifications:

Source: Richard L. Fox and Jennifer L. Lawless, “Entering the Arena? Gender and the Decision to Run for Office,” American Journal of Political Science 48: 2(April 2004), p. 273.

Source: Richard L. Fox and Jennifer L. Lawless, “Entering the Arena? Gender and the Decision to Run for Office,” American Journal of Political Science 48: 2(April 2004), p. 273.

As the table shows, women who see themselves as “not at all” or “somewhat” qualified are far less likely than men who see themselves the same way to consider running for office. The yawning gap shrinks dramatically, but does not disappear, at higher qualification levels.

It’s really a double whammy. Women are not only less likely to perceive themselves as qualified but also are less likely to run even when they have the same perception of their qualifications to run for office as men.

Interestingly, Fox and Lawless argue that two suspected culprits, family responsibilities and having a more traditional political cultural outlook (i.e. being more moralistic) do not shape the likelihood of running for office after controlling for other factors such as income, age, encouragement, and self-perceived qualifications.

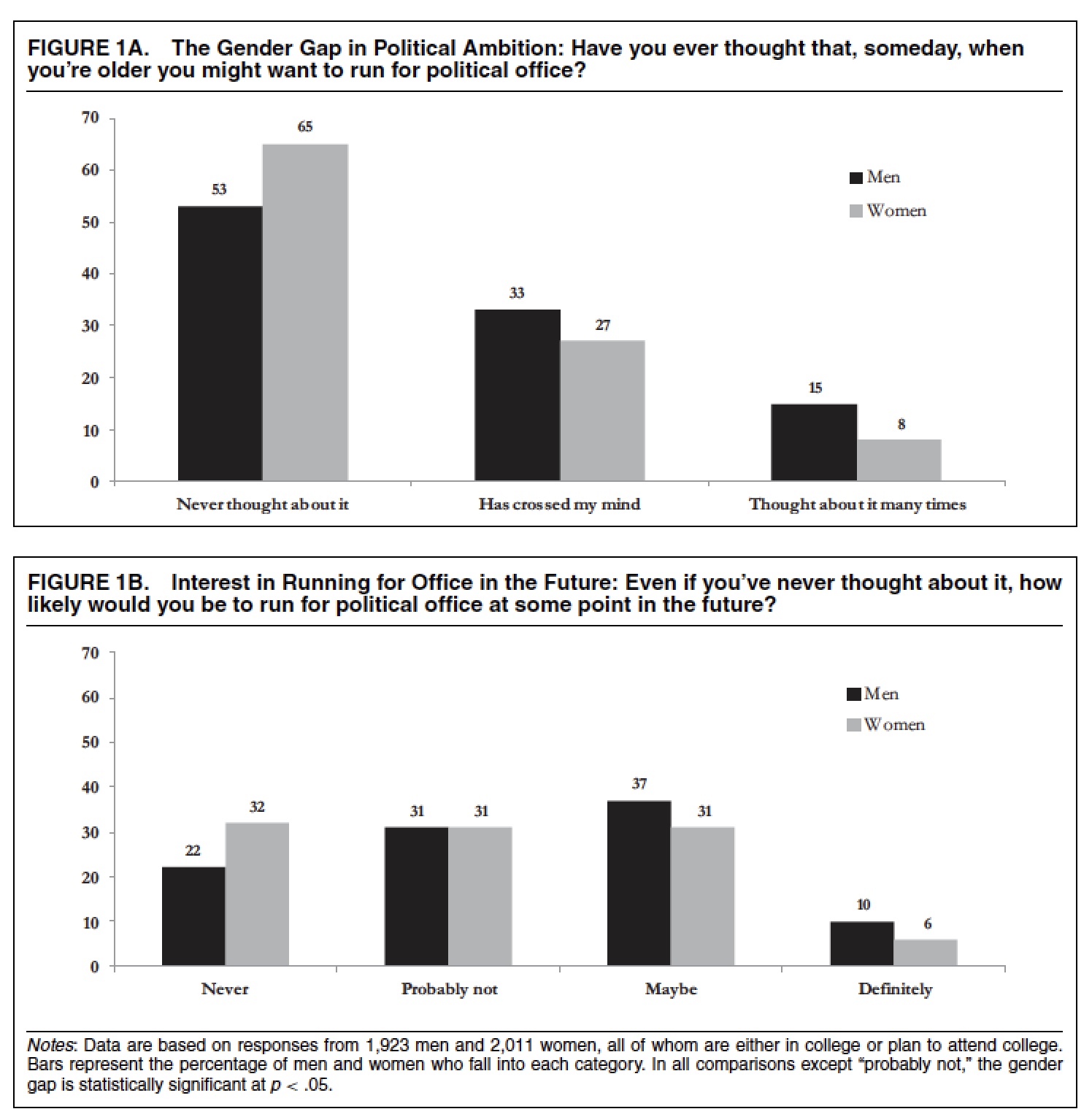

Going deeper into the subject matter, Fox and Lawless find that gender differences in political ambition surface in both high school and college students. Their survey revealed that young women are less likely than young men to think about running for office:

Source: Richard L. Fox and Jennifer L. Lawless, “Uncovering the Origins of the Gender Gap in Political Ambition,” American Political Science Review 108: 3(August 2014), p. 502.

Source: Richard L. Fox and Jennifer L. Lawless, “Uncovering the Origins of the Gender Gap in Political Ambition,” American Political Science Review 108: 3(August 2014), p. 502.

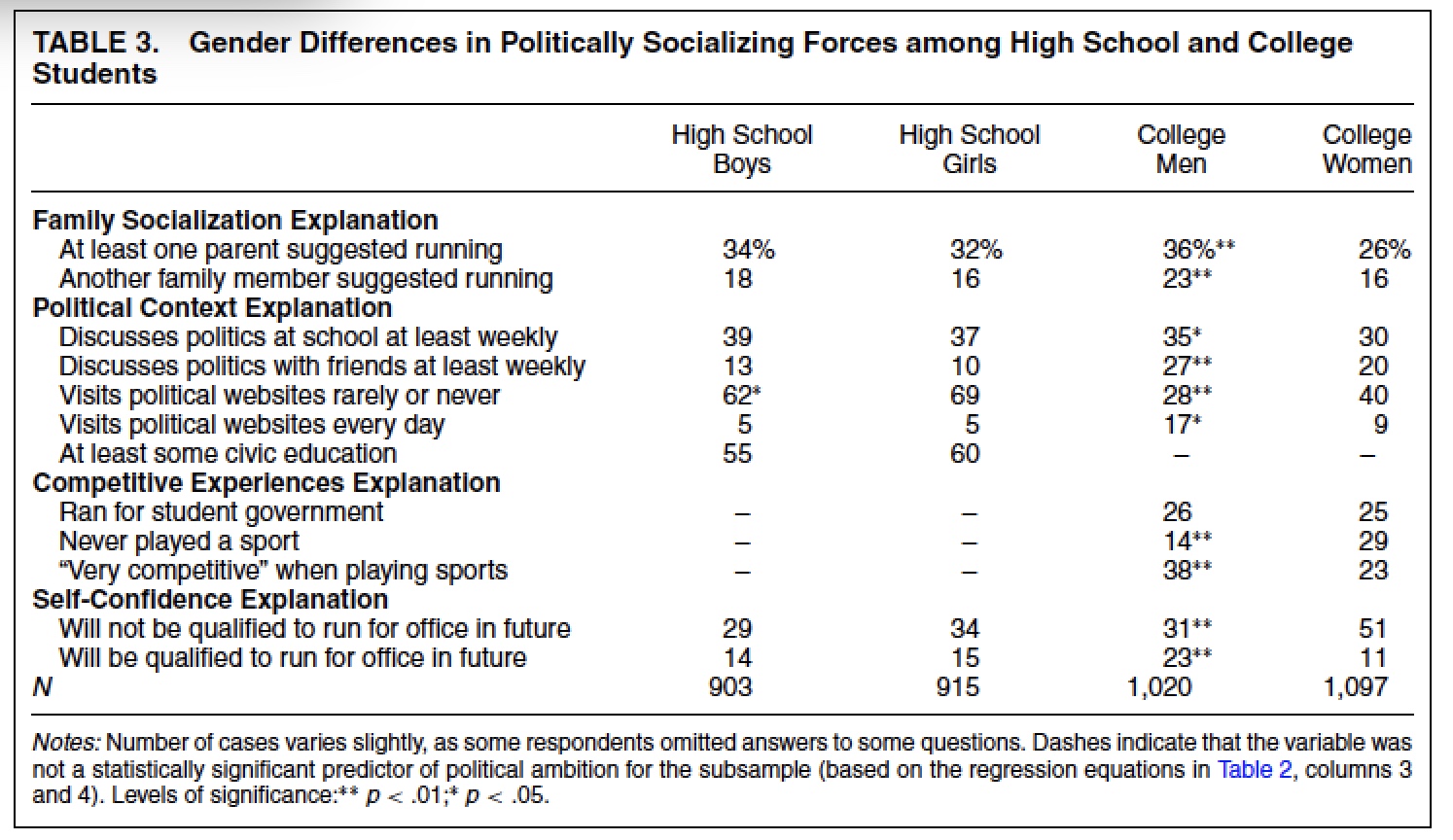

They find that gender differences that help drive these differences in political ambition are especially pronounced among college students:

Source: Richard L. Fox and Jennifer L. Lawless, “Uncovering the Origins of the Gender Gap in Political Ambition,” American Political Science Review 108: 3(August 2014), p. 510.

Source: Richard L. Fox and Jennifer L. Lawless, “Uncovering the Origins of the Gender Gap in Political Ambition,” American Political Science Review 108: 3(August 2014), p. 510.

Family members are more likely to suggest to college men that they run for office. College women are less likely to discuss politics or visit political websites. Perhaps most jarringly, college women are less likely than college men to think they will be qualified to run for office in the future.

In the final part of this three-part series, I examine how the type of office also shapes whether women run or win.