Today, I am pleased to present a guest post from Adam Pagnucco:

Rising to the defense of the county’s liquor monopoly, the County Council has put forward a proposal for reform. They claim it will cure most of the problems at the Department of Liquor Control (DLC) while causing none of the budgetary consequences of allowing full private sector competition with the department. Are they right?

Let’s examine their recommendation in detail.

The council’s proposal focuses on “special orders,” which are requests by customers for products not in DLC’s regular stock. The DLC’s performance in delivering these products is a huge source of complaints for restaurants and retailers, who claim that DLC regularly shorts orders, misses orders, delivers the wrong products and charges mark-ups that are significantly higher than in the District of Columbia. The following story is a typical description of DLC’s operations in this area.

Mike Hill, general manager of Adega Wine Cellars & Café in Silver Spring, said they have problems getting specialty wines and craft beer.

“If we like a beer or wine and we want to bring that into our store, the turnaround time can be eight days if we’re lucky or two to three months to not at all in some cases,” Hill said.

He said delivery times vary from 11 a.m. to 7:30 p.m. He explained that sometimes he receives orders that should have gone to other restaurants or stores. Other times his business receives sealed boxes that are labeled as one type of wine, but turn out to be another type when they open it.

“About 75 percent of my wall is bare because of items we’re unable to get,” Hill said.

The council is right to be concerned about this. Their proposal would allow retailers and restaurants to purchase specialty wines and beer directly from private distributors. That sounds great on the surface, but the devil is in the details. Let’s have a look at the major features of what the council has in mind.

- DLC remains in control.

DLC has sole authority to determine what beverages are regular stock or special order, and the council’s proposed legislation does nothing to change that. DLC would also have sole authority to levy and administer a fee on any transactions between private customers and private distributors, an issue explored further below. Because DLC continues to preside over, control and impose charges on any purchases under the council’s proposal, that guarantees that its many inefficiencies will continue to plague the entire system.

- The economics don’t work.

The council would have private distributors make small deliveries of specialty products while retaining most of the volume for direct delivery by DLC. That’s a problem. Distribution is a capital-intensive industry. Assets like warehouses and trucks are expensive to maintain. To make money, distributors need to move lots of volume through their warehouses and send out lots of full trucks. If they can’t do that, many won’t be able to profit under the council’s proposal and they could simply stay out. Since distributors strike exclusive arrangements with manufacturers, this factor alone could exclude many beverages from the council’s proposed new system, thereby limiting its scope and defeating its purpose.

The two largest distributors in Maryland, Reliable Churchill and Republic National, made this argument in a July 2015 letter to the county council. They wrote:

We suggest that some wholesalers, including us, will not be able to deliver special orders for economic reasons. At present, private wholesalers deliver only to the Department of Liquor Control (the “Department”) warehouse so they have no regular delivery routes in the County. To fulfill a special order, the private wholesaler would have to make a special trip to the licensee. By their nature, special orders are for small quantities. The profit on such a small transaction would not cover our delivery costs incurred by sending a truck for a special delivery. In other words, there is no financial incentive to make the special delivery and, in fact, a disincentive.

We do not want the [council’s] resolution to raise expectations unnecessarily, so we are writing again. As you know, private wholesalers are not required to fill all orders. Also a winery and distillery can use only one private distributor in Maryland. A distributor can refuse to fill an order if it is not economically feasible. Common sense dictates that a private wholesaler would not fill orders costing them money because they are not in business to lose money. It is almost certain that Republic National and Reliable cannot afford to make a special delivery to a licensee.

- The do-nothing fee.

The most controversial aspect of the council’s proposal is that DLC would be able to charge a fee on any special order transactions between private customers and private distributors even though it does nothing to facilitate them. According to the council’s legislation, the fee would be “set at a level sufficient to replace the Department of Liquor Control for Montgomery County’s estimated revenue lost by allowing private licensed Maryland wholesalers to sell and distribute beer and light wine products…” So DLC would be made whole. It would be the sole determiner of exactly how high of a fee would be required to make it whole. And since DLC is hugely inefficient in the special order segment – something even the council admits – the fee would reflect DLC’s bloated service costs rather than any cost savings obtained by going private. And who would ultimately wind up paying this fee? That’s right, the consumer.

Here’s what the state’s two largest distributors wrote about the do-nothing fee (which they characterize as a tax) in the letter shown above.

We also suggest that the local tax you intend to impose on special orders is counter-productive. It makes a bad economic situation worse. First, increasing the cost of products will encourage people to shop outside the County, thereby creating a hit for County business. The County should lower prices to keep business in the county. Already, tens of millions of dollars are spent outside the county on alcoholic beverages due to the comparatively higher costs. Second, the tax makes delivery of a special order even more costly, discouraging wholesalers from delivering special orders. Wholesalers cannot charge more in Montgomery County to recoup a local charge. Third, state law precludes local taxation of alcoholic beverages, thereby suggesting that the local charge is illegal and cannot be implemented. Fourth, we expect significant opposition to this proposal of a local charge based on its statewide implications. Last, in some ways, the County should pay wholesalers to deliver special orders because they are solving a County problem at their expense. We know that will never happen.

What if the do-nothing fee is removed? Well, there’s a catch: the county issues bonds backed by liquor profits. The council and the County Executive use this as a basis for opposing full private competition but it’s also relevant to the council’s proposal. The County Executive believes that the do-nothing fee is required to protect those bonds in the case that any liquor distribution is done privately. In the memo below, the Executive writes to the Council President:

I have been advised by the County’s Bond Counsel that edits were required to earlier drafts of the [liquor control] legislation to avoid a downgrade to the over $100 million in outstanding Department of Liquor Control (DLC) Revenue bonds as well as prevent litigation from existing bondholders due to a material deterioration in the security of the bonds. According to Bond Counsel, at the time the bonds were sold bondholders had the security of a near monopoly created by State law. If this legislation is approved that near monopoly will no longer exist under State law; so the security of the bonds will have changed. Prior drafts of the legislation did not limit the reduction in DLC revenues pledged for the payment of the bonds and did not mandate the imposition of the surcharge [on private transactions].

The best option for reducing the possibility of a downgrade or a bondholder action is to require that the surcharge collected from the wholesalers is equal to lost revenues. Therefore we have inserted provisions making the surcharge mandatory and “set at a level sufficient to replace… the estimated revenue lost.” This provision should remain even after the bonds have been paid to protect County services supported by the DLC earnings transfer.

And so if the council’s recommendation is adopted with a do-nothing fee, it will – surprise! – do nothing because distributors won’t participate. And if it is adopted without one, it would cause many of the same budgetary issues as an End the Monopoly approach with few of the offsetting benefits.

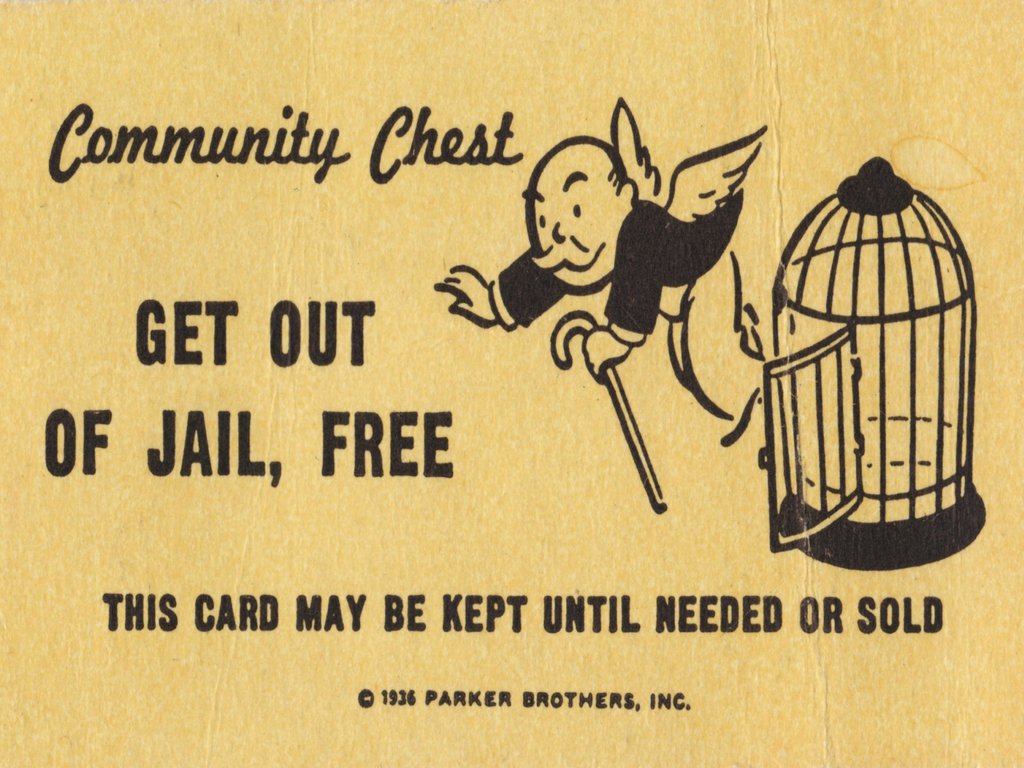

- A Get Out of Jail Free Card for DLC.

Remember the board game Monopoly? One of its most famous playing cards allows a player to Get Out of Jail Free. That’s exactly what the council’s proposal does for DLC.

The proposals by Comptroller Peter Franchot and Delegate Bill Frick would expose DLC to full private sector competition – the only force that will compel DLC to improve. But the council’s system would keep DLC in the driver’s seat. DLC would decide which beverages to sell, which ones to delegate to the private sector and exactly how much money it will charge to be “compensated.” It will remain free to run its warehouse with sticky notes and to suffer shortages of as many as 154 cases a day. Its broken ordering system will now include extra accounting and paperwork to administer the do-nothing fee. And if anyone speaks up in the future in favor of real change, the DLC’s bureaucracy will say, “Wait a minute. A new procedure has just been put in place. We need time to implement it. And once we do, we promise things will improve.” And a year will pass. And five years. And then a decade. And businesses will continue to struggle while consumers simply flee to the District of Columbia, which they do now.

The council’s proposal is designed to force citizens – consumers and businesses alike – to subjugate their interests to the liquor monopoly. Good government demands the opposite: the county should serve the interests of the citizens. And there’s only one way to do that.