By Adam Pagnucco.

As MoCo faces a crippling financial shortfall projected at $190 million this year and a billion dollars over the next six years, the county council will be considering increased spending in legislation tomorrow – on political campaigns. The issue at hand is a change in public financing matching formulas that would send more taxpayer dollars into politicians’ campaign funds.

As currently written, the county’s public campaign finance law sends matching funds to participating campaigns for individual contributions made by county residents up to $150. The current formulas appear below.

County Executive candidate

First $50 of individual contribution: matched by 6 public dollars for each dollar collected from a resident.

Second $50 of individual contribution: matched by 4 public dollars for each dollar collected from a resident.

Third $50 of individual contribution: matched by 2 public dollars for each dollar collected from a resident.

County Council candidate

First $50 of individual contribution: matched by 4 public dollars for each dollar collected from a resident.

Second $50 of individual contribution: matched by 3 public dollars for each dollar collected from a resident.

Third $50 of individual contribution: matched by 2 public dollars for each dollar collected from a resident.

In the current system, individual contributions are capped at $150 so no matching funds are made available for contributions greater than that amount. Individuals from outside the county may contribute up to $150 each but such donations are not eligible for matching funds. Contributions from entities other than individuals (like businesses and PACs) are prohibited for candidates in public financing. Self-funding of up to $12,000 from a candidate and spouse combined is permitted. Future contribution limits will be updated in future election cycles for inflation.

Bill 31-20, a package of changes to the public financing law, is on the council’s agenda for action tomorrow morning. For the most part, the bill makes a series of benign tweaks to the law. But it does one thing that increases the cost of public financing: it raises eligible individual contributions from $150 to $250 and creates a dollar-for-dollar public match to the hundred dollar increase. So for a candidate accepting a maximum individual contribution, the matching funds formula would be:

County Executive candidate

Old system: $150 individual contribution, $600 public matching funds, $750 total.

New system: $250 individual contribution, $700 public matching funds, $950 total.

County Council candidate

Old system: $150 individual contribution, $450 public matching funds, $600 total.

New system: $250 individual contribution, $550 public matching funds, $800 total.

How much more would this cost the taxpayers? That’s hard to estimate. The bill’s fiscal note assumes that everyone who gave the maximum $150 contribution in 2018 would give a $250 contribution if allowed and uses the 2018 election as a baseline. (Those are big assumptions, but the fiscal note is what it is!) Using those criteria, the fiscal note estimates that matching funds for $250 contributions would have generated an extra $487,034 in taxpayer costs in 2018, or a 9% increase.

Now let’s not set that number in stone. First, 2018 saw a genuinely contested county executive general election, a very rare event in MoCo politics. Second, there is no guarantee that 2022 will see as many candidates as last time primarily because there may be only one open at-large seat following three open at-large seats in 2018. Third, if Question C (which adds two district seats) passes, there will be more open seats, more candidates and more costs. So if passed, the bill’s extra costs could be higher or lower than the fiscal note’s estimate. But there will be extra costs compared to the current regime.

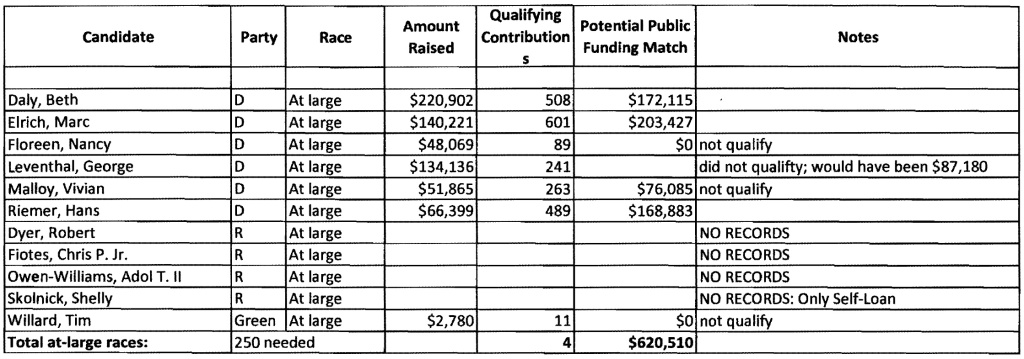

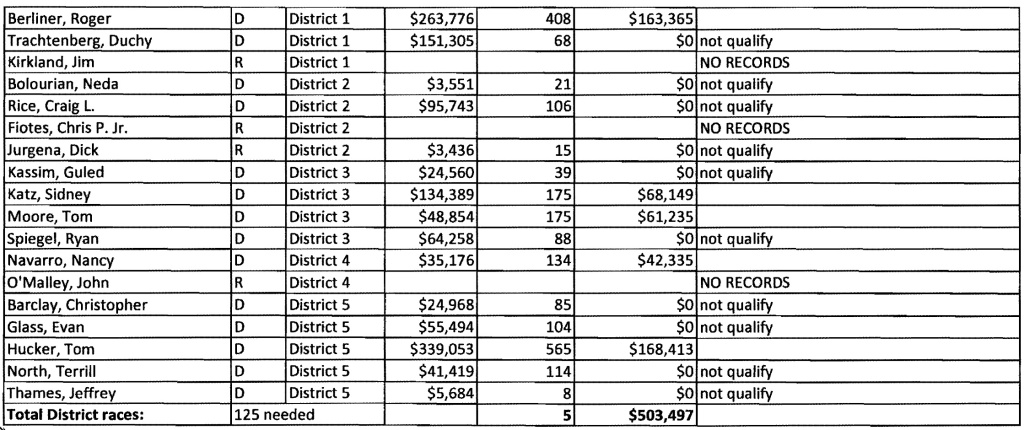

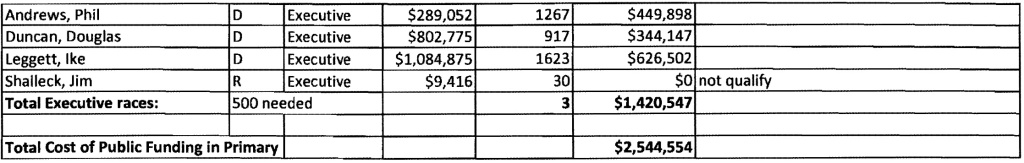

Why does the bill increase both the maximum individual contribution and the matching funds? There is no reason to believe that public financing levels are inadequate. Six of the nine sitting council members and the county executive used public financing two years ago. All of them faced opponents using traditional financing and still won. The winning candidate for county executive, Marc Elrich, raised $1.9 million in public financing combining the primary and general elections. Four council at-large candidates in public financing (Will Jawando, Evan Glass, Hans Riemer and Bill Conway) raised more than $300,000 each, which is comparable to past totals of leading candidates in the traditional system. Two more (Gabe Albornoz and Hoan Dang) raised more than $250,000. Jawando raised more than $400,000. Again, there is no shortage of money here.

As part of its process in considering the bill, the council surveyed eleven candidates who used public financing in 2018 on their views of necessary changes. Just three candidates recommended increasing the public matching amount and only two candidates recommended increasing the maximum donation. There was little demand for this cost increase. Nevertheless, it somehow made it into the bill. All three members of the Government Operations Committee supported raising the maximum donation from $150 to $250. Sidney Katz and Nancy Navarro voted in favor of a dollar-for-dollar match for the difference between $150 and $250 while Andrew Friedson voted against a funding match for the new hundred dollar increment.

Arranging for what could be a substantial cost increase in public financing – an increase that would be even larger if Question C passes – while at the same time adding council staff, refusing to fund collective bargaining agreements and perhaps making program cuts in the near future would not be a good look for the county council. The council is also being closely watched by advocates of Question B (which would cap property tax growth) and Question D (nine council districts), all of whom will use spending increases for politics to bolster their messages. Raising the contribution limit is one thing; it costs taxpayers nothing. But the council should hold off on changing funding formulas to spend more taxpayer money on their political campaigns.