By Adam Pagnucco.

Montgomery County’s 2018 primary is now roughly a year away. Many uncertainties have yet to be decided. But one thing is for sure: the two most influential people in the election are not on the ballot. One is the current occupant of the Oval Office. The other is a retired County Council Member whose towering legacy will affect everyone running for county office one way or another. He is the last person who would ever make such a claim, so we will do it for him. He is Phil Andrews.

Andrews was a former Executive Director of Common Cause who ran unsuccessfully for council at-large in 1994 but was elected after defeating an incumbent in District 3 four years later. Early in his career, Andrews was a progressive darling, passing a living wage law and a restaurant smoking ban in his first term. Later, he became known for fiscal prudence and authored the county’s public campaign financing law in his last year at the council. Andrews finished third in the 2014 County Executive Democratic primary with 22% of the vote and is now employed by the State’s Attorney’s office.

Andrews’s shadow looms large over the coming election in three ways.

Public Campaign Financing

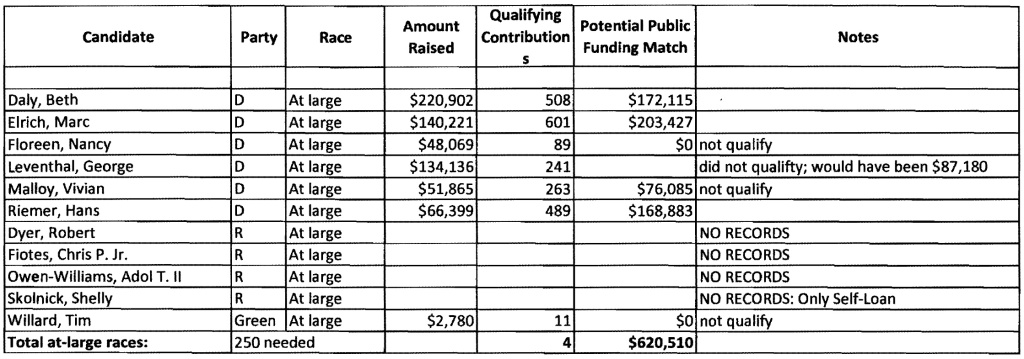

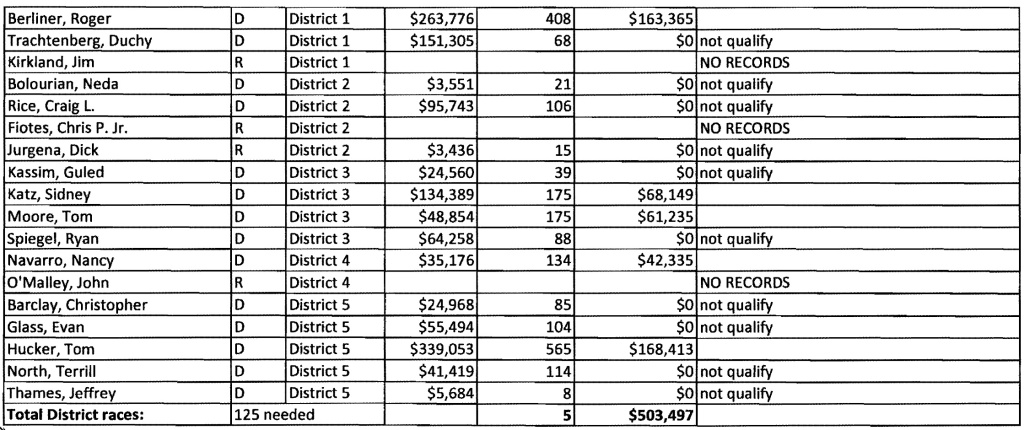

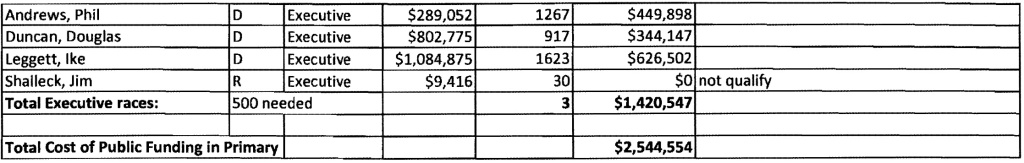

During his career, Andrews never accepted campaign contributions from PACs or developers. He wrote the county’s public campaign financing law in part to allow candidates following his example to be competitive with traditionally financed rivals. The growing number of candidates who are using it testifies to its popularity. One at-large council candidate, MCPS teacher Chris Wilhelm, even has a petition demanding that all county candidates enroll. One thing is for sure: all county candidates, whether they use it or not, will have to deal with its political implications.

During his time in office, Andrews was surrounded by colleagues who freely accepted money from PACs and developers. Now some of those same people are enrolling in public financing. Andrews must feel like a country pastor welcoming reformed sinners to church.

Opposition to Tax Hikes

After having been in office for a few years, Andrews became concerned that growth in the county’s budget was unsustainable. He began opposing what he viewed as excessive spending, especially on union contracts, and started working against tax hikes. In 2008, Andrews teamed up with at-large Council Member Duchy Trachtenberg to reduce the size of a proposed property tax hike. Two years later, he voted against a county budget partly because it raised the energy tax.

The conventional wisdom is that opposition to the 2016 tax hikes was responsible for passing term limits, although the truth is probably more complicated than that. Still, the majority of Democrats voted for term limits and that fact is not lost on new candidates for office. Several of them are leery of more tax hikes and more than one will make an issue of it during the next election. One potential at-large candidate recently told your author, “I will be the hardest vote to get for any tax hike.” Reggie Oldak, running in District 1, has said, “We can’t keep increasing property taxes.” Neil Greenberger, the County Council’s now-former spokesman, openly denounces the 2016 increases. There will be others making similar arguments.

How many components of Phil Andrews’s 2014 message will show up in next year’s election? Our bet: lots.

Temperament and Demeanor

In our conversations with those who are running or thinking of running for county office, we have often asked who their favorite Council Member is. Hands down, the winner is Phil Andrews. That choice is made regardless of ideology and even whether the candidate is using public financing. The most common reason cited is his temperament and demeanor in office.

“Phil was a grown-up,” said one candidate. Another said, “He could disagree without fighting. It was never personal.” A third said, “He never BS’d you. He told you what he thought and that was it.” That’s all true. His lack of pretentiousness is also mentioned. Indeed, Andrews chose to conduct his first interview with your author years ago in the most humble venue imaginable: the council cafeteria. No steak or cocktails for him (or sadly, for me)!

Andrews looks particularly good in comparison to those politicians who argue with constituents or block them on Facebook. In one respect, that was easy for him: Andrews was almost never on social media. Even so, your author has yet to find a constituent who describes Andrews as being anything other than polite and cordial. Regardless of his personal feelings – and there were certainly some who tried to get his temperature up – Andrews never took the bait.

While some candidates will cite Andrews on the campaign trail and perhaps even seek his endorsement – probably fruitlessly – there will never be another one exactly like him on the council. His combination of tax skepticism, willingness to do battle with labor, resistance to factionalism, total invulnerability to peer pressure and raw humility is an unusual one in local politics. But Andrews will be able to look at the next council and see fragments of his influence everywhere, with different pieces appearing in different members. Somewhere deep in the rectory, the country pastor just might smile.