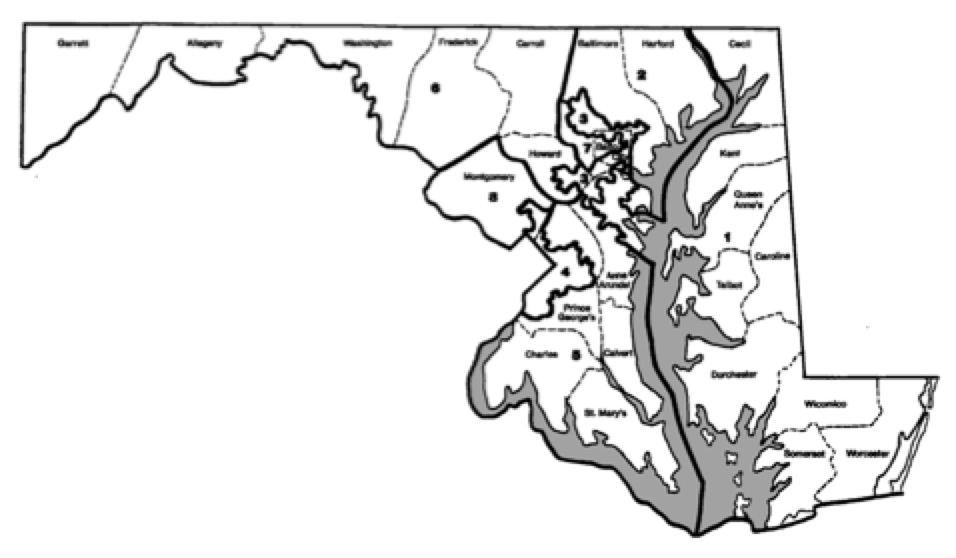

In previous posts, I’ve contended that Maryland’s extremely non-compact districts are nonetheless less skewed to the Democrats than many think. Moreover, compactness and non-partisan maps don’t necessarily result in fair outcomes.

Today, I look at the role of redistricting in promoting competition and responsiveness. The argument in favor rests on the idea that competition is the lifeblood of democracy. It helps voters keep politicians accountable. When voters swing away from one party and to another, the results should reflect the change.

It may seem odd to take into account whether a plan creates competitive districts. However, the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission operates under a mandate to prioritize them. It would also potentially result in greater shifts in House seats with changes in the vote for the U.S. House.

Not all agree that competition and responsiveness are a good thing. Tom Brunell has provocatively argued that mapmakers should create as many ultra-safe districts as possible. He points out that fewer voters cast ballots for the losing candidate–and therefore are happier with the outcome–in safe districts.

Let’s work with the other side of the argument, as I suspect more prefer responsiveness to changes in voting behavior rather than static outcomes no matter the election results. How well does Maryland’s current plan promote competition (i.e. close elections) or responsiveness (i.e. changes in seats won with changes in voting behavior)?

Not well. In 2012. the closest race was in the Sixth where challenge John Delaney ousted incumbent Rep. Roscoe Bartlett by 21 points. The next closest race was in the Eighth where Rep. Chris Van Hollen won reelection from his redrawn district by over 30 points.

If Republicans have a problem with the map, it should not be that it is inherently unfair. After all, if Maryland Republican candidates could win one-half of the votes, they likely carry one-half of the seats. Nevertheless, the plan doesn’t look likely to respond to less major changes in the electorate.

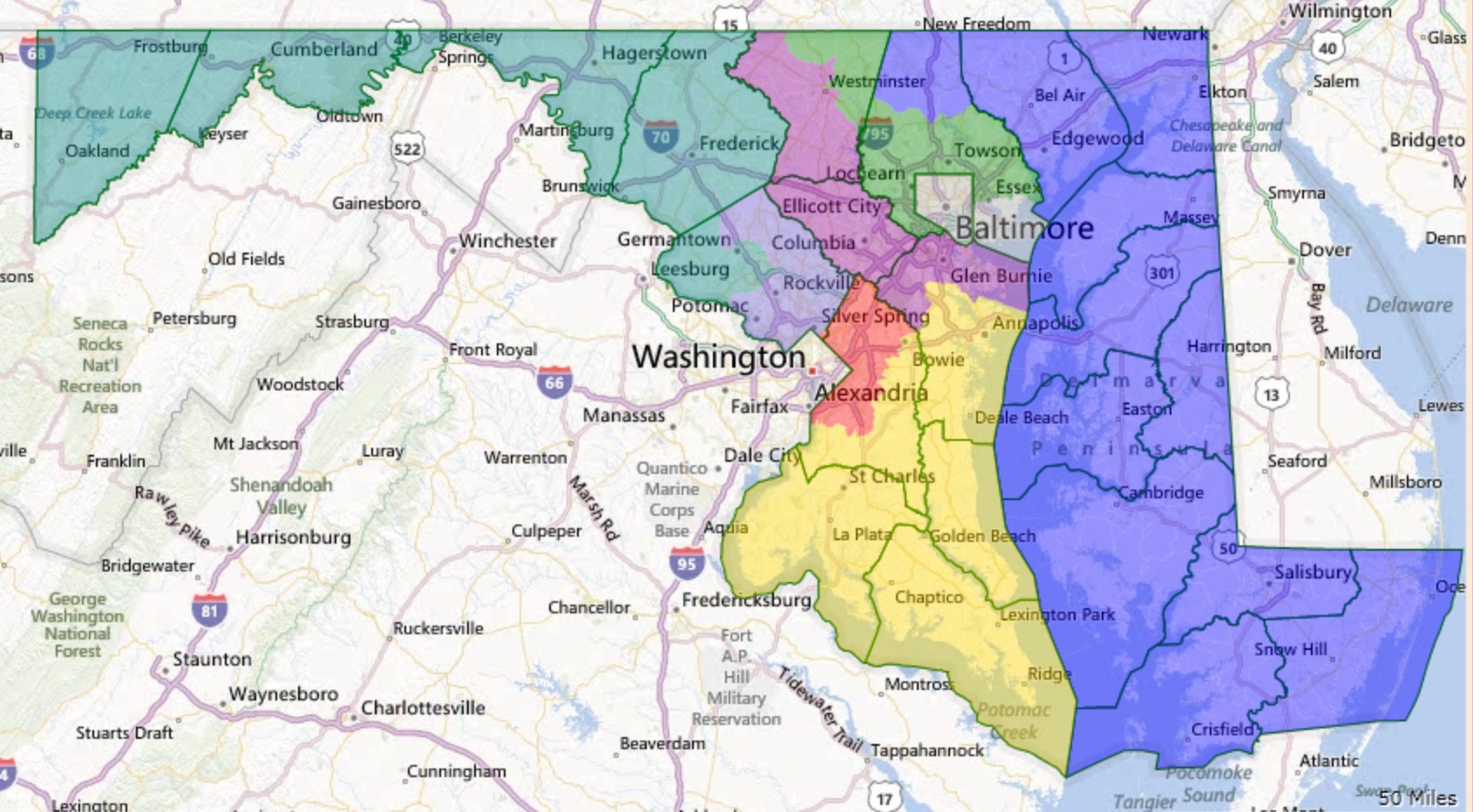

Below is a rough draft of a plan that reflects the Democratic edge but is likely to be more responsive to changes in electoral outcomes:

More Competitive Congressional Redistricting Plan

More Competitive Congressional Redistricting Plan

President Obama won a majority in 2008 in seven of the eight districts. However, his victory level was not nearly as high in several of the districts as under the current plan:

In this plan, the Republicans would need a shift of only 1.9% to gain the Third District and 3.0% to gain the Sixth District. One can imagine regular heated competition for both districts with them changing hands depending on the vicissitudes of the electorate.

In this plan, the Republicans would need a shift of only 1.9% to gain the Third District and 3.0% to gain the Sixth District. One can imagine regular heated competition for both districts with them changing hands depending on the vicissitudes of the electorate.

This plan would also be far more compact and violate fewer county boundaries than the current plan. The 1st would contain the entire Eastern Shore along with Harford and a bit of northern Baltimore County. It does not cross the Bay Bridge. The Seventh, a 54% black voting-age population district, would include all of Baltimore City along with a chunk of neighboring Baltimore County.

The new 2nd would take in the remainder of Baltimore County along with a bit of neighboring Carroll. The 8th is entirely in Montgomery County. The 6th includes all of western Maryland along with almost all of the rest of Montgomery. The 4th, a 61% black VAP district, is almost entirely in northern Prince George’s.

Finally, the 5th is composed of southern Maryland, the rest of Prince George’s and southern Anne Arundel. The 3rd becomes a central Maryland district with all of Howard, northern Anne Arundel and most of Carrol Counties.

The major problem with this plan is that is most likely too favorable to the Republicans. A gain of 7.8% of the vote would allow the GOP to win one-half of the districts even though they would fall far short of the vote share required for an even statewide split.

They might even win all four with an even smaller percentage as the new versions of the 2nd, 3rd, and 6th contain above average shares of white voters. This matters because whites are more likely to shift way from the Democrats when a pro-Republican wind blows than black voters, who are highly concentrated in the 4th and 7th.

So greater competition and responsiveness not always conducive to partisan fairness. However, one might be able to construct a plan that better meets both requirements, though that could result in less compact districts.