The new Democratic congressional map is political malpractice in the first degree.

Both parties have aggressively pursued gerrymanders this year—Democrats in New Mexico, New York and Illinois—Republicans in North Carolina, Ohio, Texas and Wisconsin—to take a few examples. The critical difference, however, is that the Democrats have proposed a national ban on gerrymandering, while Republicans remain adamantly opposed.

Gov. Larry Hogan has lambasted creative Democratic line drawing in Maryland, where such attitude benefits his party, but is hardly an avatar of reform. He has studiously avoided commenting negatively about Republican gerrymanders elsewhere or endorsing national legislation to address the problem.

Good government promoters along with newspapers like the Washington Post and New York Times piously inveigh against gerrymandering by either party. Except at this point, given the unashamed efforts by Republicans to gerrymander wherever they can—and fighting national efforts to ban it—Democrats choosing to abandon it is unilateral disarmament. The distribution of Democrats already works to the benefit of Republicans, but Republican gerrymandering is designed to assure partisan lockups by the GOP whether the voters agree. This is already the case in the Wisconsin legislature.

Which brings me to Maryland.

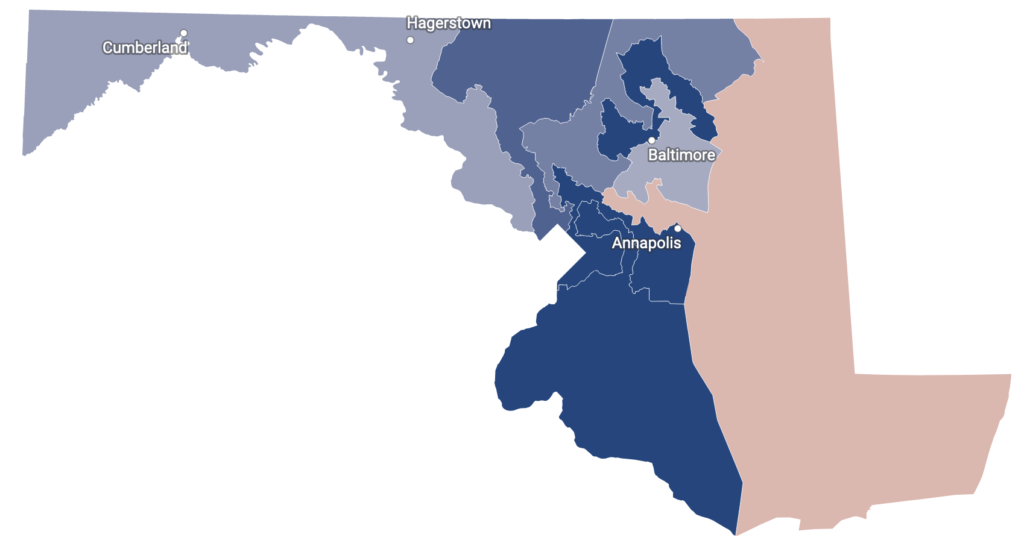

General Assembly Democrats decided to reconfigure the districts to render the First District a toss up (at best) for their party rather than a safe Democratic seat. Some of the potential reasons were outlined in a piece appearing in Slate:

[Rep. John] Sarbanes is also the lead sponsor of the For the People Act, or H.R. 1, which includes as a central plank an end to partisan gerrymandering and a national move to independent, nonpartisan redistricting commissions. As a national crusader against gerrymandering, he couldn’t bring himself to go full 8–0, several Democratic sources said. . .

[Rep. Kweisi] Mfume was concerned that absorbing chunks of largely white Republican voters into his district from Harris’ would distract from his representation of majority-minority communities in Baltimore. He was adamant against suggested changes, like stretching his district north to the Pennsylvania border. . .

[The Maryland Legislative Redistricting Commission] settled on the seven-Democrat map with a more competitive 1st District. This one still extended Harris’ district across the bay to Anne Arundel County—but curiously excised Annapolis, the inclusion of which would have been quite helpful to the Democratic candidate challenging Harris. Several sources cited one factor: The Democratic state senator representing Annapolis, Sarah Elfreth, didn’t want a competitive congressional district like the 1st layered atop hers. (“Sen. Elfreth had no role,” her staff told me when asked about this factor.)

In contrast, Reps. Steny Hoyer and Jamie Raskin were described as fully on board with an 8-0 map.

In the end, General Assembly Democrats settled on a map that is truly the worst of all worlds. They drew a district that has an excellent chance of reelecting Rep. Andy Harris—an ivermectin prescribing, coup friendly representative. Yet the lines are sufficiently ugly that no one is going to give them “credit” for not gerrymandering. Is Rep. Sarbanes really so benighted that he thinks he looks good because he stopped Democrats from gerrymandering more?

Indeed, the map preserves some of the old plan’s more derisory elements, such as the Hoyer hook that swings the Fourth into College Park completely unnecessarily. And Third District Rep. John Sarbanes will represent Harford and Montgomery Counties.

To those who say it is unfair to have an 8-0 map, let them get a national gerrymandering ban passed. It’s a great overdue idea that’s languishing due only to Republican opposition.

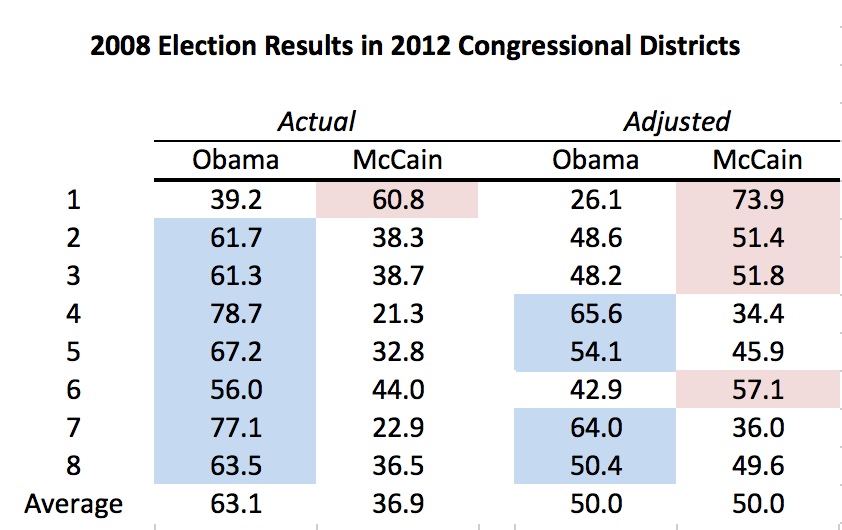

In the meantime, an 8D-0R map in Maryland, where Biden won 65-32 seems a lot fairer than the projected 11R-3D map in 50-49 (Trump) North Carolina, 9R-5D map in 50-49 (Biden) Georgia, or 12R-3D map in 53-45 (Trump) Ohio. Republicans also seem unbothered by the Democratic shutout in Oklahoma, which Trump by the same margin as Biden won Maryland.

Meanwhile, the maladroit gerrymander passed by General Assembly Democrats no doubt has many people rolling their eyes either because it’s a gerrymander or because it’s such an incompetent one. SMH.