With the early vote already counted in Montgomery County, terms limits is now leading by 64% to 36%. At the same time, the Council’s amendment to not count Nancy Navarro’s partial term is also currently ahead by 80% to 20%.

Tag Archives: Montgomery County

MoCo’s Two Electorates, Part Three

By Adam Pagnucco.

Part Two presented a host of demographic data comparing Democrats who voted in all three of the 2006, 2010 and 2014 primaries (“Super Dems”) to voters from all parties who voted in both of the 2008 and 2012 general elections (“Super Generals.”) Let’s compare the two groups more concisely below.

In summary, when compared to Super Dems, Super Generals are more likely to:

- Be age 29 or younger.

- Be ages 30-39.

- Live in Clarksburg.

- Live in Damascus.

- Live in Germantown.

- Live in Council District 2.

- Live in Legislative District 39.

- Live in precincts that are 25% or more Asian.

- Live in Legislative District 15.

- Live in Montgomery Village.

When compared to Super Dems, Super Generals are less likely to:

- Be ages 70-79.

- Be age 80 or older.

- Live in Takoma Park.

- Live in Chevy Chase.

- Be ages 60-69.

- Live in Legislative District 20.

- Live in Bethesda.

- Live in Kensington.

- Live in Legislative District 18.

- Live in Council District 5.

The above items are ranked in order of likelihood. So for example, the biggest difference between the two electorates is in age, but that is far from the only difference.

Super Dems are mostly from Downcounty, tend to be seniors or close to it, have a lot of voting history and may be majority liberal. They elect MoCo’s county officials and state lawmakers, who tend to be responsive to them. Super Generals are geographically diverse, younger in age, have less voting history and are much more diverse ideologically. Liberals probably do not account for a majority of Super Generals. It is the Super Generals, not the Super Dems, who decide charter amendments and ballot questions, including this year’s amendment on term limits.

Two more facts are relevant to Super Generals.

First, on the last three major county ballot questions, the general electorate voted in favor of stricter limits on property tax hikes, against the ambulance fee and against broad collective bargaining rights for the police union. These were arguably the less progressive positions on all three questions. If these questions were submitted only to Democratic primary voters, they may all have had different outcomes.

Second, a Washington Post poll in September found that MoCo voters from all parties together gave Governor Larry Hogan a 66% job approval rating. This was not significantly different from the Governor’s statewide approval rating of 71%. It’s hard to imagine a majority progressive electorate approving of an anti-tax GOP Governor to that extent, but this is further evidence that liberals may not in fact be a majority of MoCo voters.

Term limits is the issue of the day and will be decided soon enough. But a broader question looms. Given the differences between MoCo’s Two Electorates, what happens when elected officials cater to one of them at the heavy expense of the other? The recent large property tax hike, which was spread all across county government, was aimed at the priorities of liberal Democratic voters. It also became the core of the push for term limits which is aimed at the general electorate. This suggests a need for balance and restraint by those running the government. Because if one of the two electorates feels unheeded, either one has the tools to strike back – either by unseating incumbents or by shackling them with more ballot questions and charter amendments.

MoCo’s Two Electorates, Part Two

By Adam Pagnucco.

In Part One, we began contrasting MoCo’s Two Electorates: namely, the Democratic primary voters who pick our elected officials, and the general election voters who decide charter amendments and ballot questions. Today we present new data on the two electorates from the voter file.

We have integrated the January 2015 voter file available from the county’s Board of Elections with a variety of U.S. Census demographic data to analyze two groups of MoCo voters. The first group, whom we call “Super Dems,” are those Democrats who voted in all three of the county’s 2006, 2010 and 2014 primaries. The second group, whom we call “Super Generals,” are those voters from all parties who voted in both the 2008 and 2012 presidential general elections. We would have also included 2004 voters if we could have, but the voter file doesn’t go back that far. Presidential general election voters are relevant to this year, which is also a presidential year in which term limits are on the ballot.

Let’s look at a few demographics for Super Dems and Super Generals.

Party Affiliation

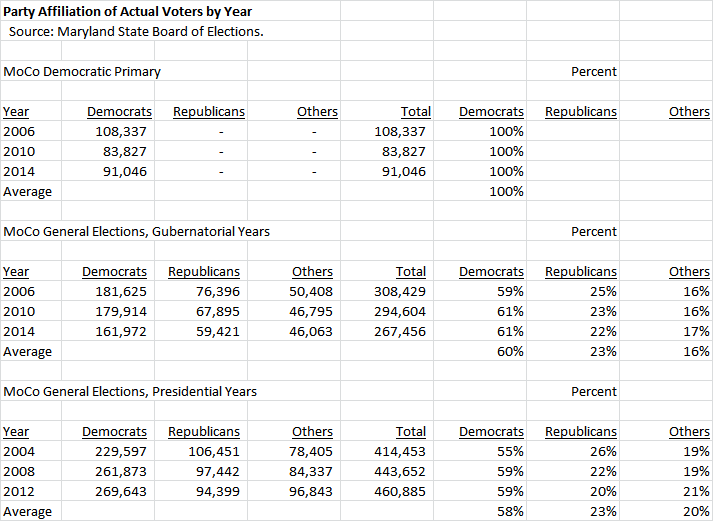

Super Dems are, of course, 100% Democrats. Super Generals are 60% Democratic, 21% Republican and 18% others (most unaffiliated voters). This matches the distribution of general election votes referenced in Part One.

Gender

Both groups are majority female, with women being a slightly higher share of Super Dems.

Age

Super Dems skew towards seniors, with an average age of 64. Super Generals are much more diverse on this measure, with an average age of 55. While 19% of Super Generals are below age 40, only 3% of Super Dems are. And while 63% of Super Dems are age 60 or older, only 39% of Super Generals are. This means that while young voters are a meaningful voting bloc in general elections, they generally are not in MoCo Democratic primaries. The difference in average date of voter registration in the county further emphasizes the deeper roots Super Dems have in MoCo than Super Generals.

Average Household Income

This is not a significant differentiator between the two groups, although this data masks real differences in residence geography.

Residence Type

This is also not a significant differentiator. Both groups overwhelmingly live in single family homes and a big majority of them are probably home owners.

Location of Residence

Super Dems are more likely to live in Downcounty locations like Takoma Park, Chevy Chase, Bethesda, Kensington and Silver Spring while Super Generals are more spread out, including in Upcounty communities like Clarksburg, Damascus, Germantown and Montgomery Village. This has ideological implications. In this year’s Congressional District 8 primary, the very progressive Jamie Raskin ran up his biggest margins inside and near the Beltway, while the more moderate David Trone did best in northern areas.

District of Residence

Once again, the geographic split between the two groups is obvious. Fifty-four percent of Super Dems can be found in the two liberal strongholds of Council Districts 1 and 5, while Super Generals are more geographically balanced. This may help explain why three of four At-Large Council Members come from Takoma Park.

Precinct Demographics

Race and ethnicity are not available from voter registration data, but we can examine those factors for the precincts in which voters live. By this measure, Super Generals appear to be slightly more diverse than Super Dems. This suggests a need for more outreach to people of color by the Democratic Party, which should be their natural home.

We will conclude in Part Three.

MoCo’s Two Electorates, Part One

By Adam Pagnucco.

Montgomery County voters are some of the most progressive people in the nation. They elect only Democrats, and almost all very liberal ones. They celebrate diversity and respect civil rights. They support a large, active government that passes liberal laws, provides excellent schools and generous social services and has extensive environmental programs. Perhaps most importantly, they are willing to pay the taxes that support all of this.

Is the above a true statement? Yes. And maybe no. It all depends on which electorate you’re talking about. Montgomery County has two of them.

The first electorate is comprised of those Democrats who vote in the closed primaries for County Executive, County Council and members of the General Assembly. Many of these are liberals who vote for candidates with similar views. Indeed, there is an old aphorism that it’s nearly impossible to run too far to the left in MoCo elections. Most elected officials here regard these voters as their political base and tend to be highly responsive to them.

But there is a second electorate: those residents who vote in general elections. These voters come from all political parties and have significant ideological diversity. For the most part, they tend not to reject the nominees of the Democratic Party for local and state office. (The last Republican elected officials here were defeated ten years ago.) But they can and do weigh in on charter amendments and ballot questions, and they do not always behave in accordance with the county’s progressive reputation.

This blog series examines the differences between these two electorates on the eve of the general election, when a landmark ballot question on term limits will be decided. Of the two electorates, only one – the general election voters – will decide whether term limits will pass.

First, we examine the party composition of the two electorates. The Democratic primary voters are of course 100% Democrats since Maryland uses closed primaries. The general election voters are roughly 60% Democratic, slightly more than 20% Republican and slightly less than 20% unaffiliated or members of other parties.

Are liberals a majority of the general electorate? That’s hard to say, but a little math can help. If just a fifth of the Democrats, who comprise 60% of general election voters, are not liberals, then a majority of the general electorate would probably not be liberal. (There are a handful of Green Party members in MoCo, but not enough to change the basic math here.) So while a majority of Democratic primary voters may be liberal, it’s difficult to apply that characterization to the entire electorate.

Another factor that can be easily seen from the data above is the relative size of the electorates. There are about three times as many voters in gubernatorial general elections as there are in gubernatorial Democratic primaries. Presidential general election voters outnumber gubernatorial primary Democrats by five to one. So while Democratic primary voters pick our elected officials, the presidential general voters are a much closer gauge of the political sentiments of the entire community.

We will begin contrasting MoCo’s two electorates in Part Two.

MoCo Board of Elections Responds to 7S Report on Early Voting Problems

The following was sent to 7S by Marjorie M. Roher, Public Information Officer of the Montgomery County Board of Elections:

Regarding “A Critical Error in Early Voting”

The Montgomery County Board of Elections would like to take this opportunity to address the concern raised in “A Critical Error in Early Voting.” Mr. Pagnucco’s description of the process that occurs in an early voting center is correct, and the Board appreciates his acknowledgement that the mistakes were honest.

Board staff learned of similar occurrences sporadically in several of the Early Voting Centers. In each case brought to our attention, the voter received the correct ballot prior to scanning and was able to cast his or her vote in the appropriate congressional race. The Election Director immediately contacted each Early Voting Center Manager to reinforce the need for accuracy in ballot distribution, instructed that Check-in Judges be reminded to circle the ballot style number on the Voter Authority Card (VAC) to make it easier to see, and Ballot Judges be reminded to double check the ballot style number on the VAC and ensure that they were issuing the correct ballot to each voter. The design of the ballot issuance tables at each Early Voting Center was reviewed to ensure that the possibility of co-mingling ballot styles was eliminated. Finally, a copy of The Seventh State blog was sent to each Early Voting Election Judge so that they might better understand the perception of the public when these types of errors occur.

All of these measures will assist in keeping errors to a minimum, but we urge voters also to pay attention to the ballot they are issued and, if they think they have the wrong ballot or if they have any other concerns regarding the voting process, speak to an election judge immediately so corrective action may be taken prior to scanning the ballot. This will assist the election judges, who are voters who volunteer to work at election time to assist their neighbors with the voting process.

When the State Board of Elections selected the voting system to be used in 2016, it intended to utilize Ballot Marking Devices (BMD) at all Early Voting Centers. This system would have allowed the Check-in Judge to hand each voter a ballot activation card with a bar code on the top, which would contain the voter’s ballot style and, when inserted in the BMD, cause the correct ballot style to appear on the screen. This would eliminate the need for an election judge to select the correct paper ballot for each voter. Unfortunately, problems with how the BMD screen displayed contests with many names could cause voters to not see all candidates before voting. For that reason, the State Board of Elections determined that the BMDs would only be used in 2016 by those individuals who requested them.

The State Board of Elections has requested the manufacturer of the BMD to modify the device so that all names in a contest would appear on the same screen. We believe that this will be accomplished by 2018 so that all voters choosing to vote during Early Voting would be able to utilize this method, thereby eliminating the need for multiple styles of paper ballots at each location and the possibility of human errors.

The Montgomery County Board of Elections strives to ensure that each voter has a pleasant, efficient, and accurate voting process and we encourage voters to contact us with comments or suggestions for improvement, so that we all can work together to make a good voting experience even better.

Marjorie M. Roher

Public Information Officer

Montgomery County Board of Elections

MoCo’s Giant Tax Hike, Part Six

By Adam Pagnucco.

Montgomery County’s giant tax hike will have consequences. Here are a few of them.

1. Term limits are more likely to pass.

There are several reasons why Robin Ficker’s newest term limits amendment will probably pass if he gathers enough signatures to place it on the ballot, but the tax hike is one of the biggest. The last time the council broke the charter limit in 2008, voters responded by passing Ficker’s charter amendment to make tax hikes harder. With a new tax hike in place, voters may be tempted to respond with term limits.

Ficker has taken notice. He regularly runs Facebook ads linking term limits, the tax hike and the council’s 2013 salary increase like the one below. Commenters respond predictably.

Ficker may have a new ally in his quest to evict the council: MCGEO President Gino Renne. After the council voted to abrogate his union’s collective bargaining agreement, Renne told the Post, “I’m tired of these clowns,” and said his union might support term limits. An alliance between Gino Renne and Robin Ficker would be one of the strangest events in the history of MoCo politics. Whoever can produce a picture of these two smiling and shaking hands will be awarded a gift certificate from Gino’s beloved Department of Liquor Control.

2. Outsider candidates could be encouraged to run for county office.

If term limits pass, two things will happen. First, the County Executive’s seat and five seats on the County Council will be open in 2018. Second, the tax increase will be blamed for the success of term limits. Both factors could lead to the entry of outsider candidates with a message like this: “We need new leadership. We need to do things differently.” Translation: we need to run the government without giant tax hikes.

Some of these outsiders may use the county’s new public financing system to run. But the strong performance of David Trone, who started with zero name recognition and won many parts of CD8, will encourage self-funders. This being Montgomery County, there are a LOT of potential self-funders, including those who have previously run for office. Candidates in public financing can raise as many individual contributions of up to $150 each as they are able to collect, but the system caps public match amounts at $750,000 for Executive candidates, $250,000 for at-large council candidates and $125,000 for district council candidates. A wealthy self-funder could easily overwhelm candidates who are subject to these caps and make a mockery of public financing.

3. More charter amendments on taxes are possible.

Ficker’s 2008 property tax charter amendment, which instituted the requirement that all nine Council Members must vote to override the charter limit on property taxes, was a mild version of his previous ballot questions on the subject. His 2004 Question A, which would have abolished the override provision entirely, failed by a 59-41 percent margin. Now that the 2008 amendment has been proven ineffective, Ficker could be encouraged to bring back his more draconian version soon. In the wake of this new tax hike, would voters support it?

Passage of a hard tax cap would have very grave consequences for the ability of county government to deal with downturns. In 2010, the County Council responded to the Great Recession by passing a tough budget combining cuts, furloughs, an energy tax increase and layoffs of 90 employees. When the next recession comes, if the county has no taxation flexibility, it might have to pass a budget laying off hundreds of people and gutting entire departments. If the levying of giant tax hikes in non-emergencies causes the voters to abolish the possibility of levying them in true emergencies in the future, it would be a serious calamity.

4. Governor Larry Hogan is a big winner.

One of Governor Hogan’s favorite political tactics is to play the Big Three Democratic jurisdictions against the rest of the state, with the City of Baltimore being his prime target. But he can also point to Prince George’s County, where the County Executive (and a potential election opponent) proposed a 15% property tax hike, and also to Montgomery County, where the council passed a 9% increase. His message to the voters will be a simple one.

“Look, folks. This is what you get when you allow liberal Democrats to have one-party rule: giant tax hikes. That’s why you need people like me in office to stop them.”

How many MoCo Democrats will ask themselves this question: “What is easier for me to live with? Larry Hogan or nine percent tax hikes?” What do you think their answer will be?

Hogan received 37% of the vote in Montgomery County in 2014. He had a 55% approval rating in MoCo according to a Washington Post poll last October. A Gonzales poll taken in March found that registered voters in the Washington suburbs (defined as MoCo, Prince George’s and Charles) gave Hogan a 62.6% job approval rating, with 35% strongly approving. If Hogan can use the tax issue to run in the low 40s, or even as high as 45% in MoCo, he will be very difficult to beat for reelection.

Reelecting himself is not Hogan’s only priority. He would also like to elect enough Republicans to the General Assembly to uphold his vetoes. That task is easier in the House of Delegates, where Democrats hold 91 seats, six more than the 85 votes required to override vetoes. If the GOP can pick up seven seats, as they did in 2014, they can uphold the Governor’s vetoes on party line votes. That would cause serious change in how Annapolis operates. Could big tax hikes in Democratic jurisdictions like Montgomery help the GOP get there?

5. It will be harder to get more aid from Annapolis.

In 2007, former Baltimore State Senator Barbara Hoffman commented to the Gazette on Montgomery County’s ultra-wealthy reputation in Annapolis. “They have to overcome the view that they’re rich and trouble-free. … That’s not true anymore.” She was right then, and she is even more right now. The county has massive needs for transportation projects and both operating and construction funds for the public schools. But when the county levies giant tax hikes on itself to pay for these needs, is it letting the state off the hook? State legislators from other cash-strapped jurisdictions that lack wealthy tax bases like Bethesda, Chevy Chase and Potomac are perfectly happy to let MoCo tax itself while they ask the state to tax MoCo even more to pay for their needs. (Remember the 2012 state income tax hike, of which MoCo residents paid 41% of the new revenue?) As a result, the next time the Lords of Annapolis are asked to help Montgomery County, they could very well reply, “Tax yourselves to pay for it. You always do.”

6. A major argument in favor of the liquor monopoly has been proven hollow.

County officials predicted that if the liquor monopoly was lost, annual property taxes would have to rise by an average $100 per household. Instead, the monopoly was preserved and the council passed a property tax hike that will cost an average $326 per household. The tax hike was in the works since at least January 2015, long before small businesses and consumers launched their campaign to End the Monopoly. And the $25 million in new spending added by the council to this year’s budget actually exceeds the $20.7 million that the liquor monopoly is projected to return to the general fund. This proves once and for all that liquor monopoly revenues do not prevent tax hikes!

7. There will be pressure in the future for another tax hike.

As we discussed in Part Three of this series, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Wynne decision, which requires counties to refund taxes paid on out-of-state income, was one reason for the current property tax hike. Senator Rich Madaleno’s state legislation extended the time that counties had to pay for refunds from Fiscal Year 2019 to 2024. Below is a table showing the fiscal impact on all Maryland counties combined, of which Montgomery accounts for roughly half. While the legislation enables counties to spend less in FY 2017-2018, it requires them to spend more in FY 2020-2024. MoCo will have to spend around $20 million a year in most of the out years.

Given its $5 billion-plus annual budget, Montgomery could easily afford the out-year payments by slightly slowing the growth rate in its annual spending. But instead, the council added $25 million in new spending on top of the Executive’s FY 2017 budget, and unless it is cut, that spending will continue in future budgets. The cumulative impact of that new spending plus future Wynne refund payments will start to be felt in three years. At that point, the council could very well face a choice between trimming back their added spending or raising taxes. What do you think they will do?

8. Economic development will now be harder.

Despite the wealth in some of its communities, Montgomery County struggles with the perception that it is not business-friendly. While its unemployment rate is low by national standards, its real per capita income fell steeply during the recession, much of its office space is obsolete and it lacks Northern Virginia’s two major airports and its new Metro line. The chart below shows the county’s private sector employment from 2001 through 2014. Despite recent sluggish growth, the county had fewer private sector jobs in 2014 than it did in 2001.

And while the county lost private sector jobs, the Washington region as a whole grew by 9.5% over this period.

There may be a variety of factors explaining MoCo’s weak economic performance, but consider this: in the last 15 fiscal years, the county has seen six major tax increases. The county broke its charter limit on property taxes in FY 2003, 2004, 2005, 2009 and 2017 and it doubled the energy tax in FY 2011. (Most of the latter increase is still on the books.)

Good government is an exercise in balancing needs. Education, transportation, public safety and public services are valuable and require resources, at times necessitating tax increases. But all of that is impossible without a vigorous private sector that creates jobs and incomes and pays the government’s bills. Those priorities must be balanced, and when they are, progressive policies can be afforded. But if they are not, economic growth will fail, government services will be harder to sustain, taxes will fall increasingly on a shrinking base and a downward spiral could begin.

In the wake of its long-term stagnant economy and its Giant Tax Hike, how close is Montgomery County to that tipping point?

MoCo’s Giant Tax Hike, Part Five

By Adam Pagnucco.

The untold story about the Giant Tax Hike is that it could have been cut substantially while still maintaining every dime of funding for MCPS in the Executive’s recommended budget. How could that have been done?

The Executive called for an increase in property taxes of $140 million over the charter limit. Three sources of savings were available to offset it. First, Senator Rich Madaleno’s state legislation enabling the county to extend the time necessary to pay tax refunds mandated by the U.S. Supreme Court’s Wynne decision freed up $33.7 million. Second, the County Council had obtained $4.1 million by not funding some elements of the employees’ collective bargaining agreements. Third, county agencies other than MCPS were due to receive a combined $36.3 million in extra tax-supported funds in the Executive’s recommended budget. Using some or all of that money for tax relief would have reduced the tax hike even more. If all of that money were redirected, the tax hike could have been cut in half with MCPS still getting the entire funding increase in the Executive’s budget.

Instead, the council kept the entire 8.7% property tax hike and distributed $25 million of it throughout the entire county government, as well as its affiliated agencies and partner organizations. While MCPS may have undergone seven straight years of austerity, most of the other agencies and departments had already received double-digit increases over their pre-recession peak amounts. This new money was on top of those increases.

Council President Nancy Floreen was very honest about this, writing:

While this is an “education first” budget, it isn’t an “education only” budget. As much as many people care about our outstanding school system, we know that others have different priorities. This budget is very much about those people as well.

This budget provides a much-needed boost to police and fire and rescue services as we will be adding more police officers and firefighters and giving them the equipment they need to continue to make this one the safest counties in America. This budget is about libraries, recreation, parks, the safety net, Montgomery College, and transportation programs that help get people around this county better.

This budget means that no matter where you live in the county, if you call an ambulance, you can count on a life-saving response time. Our police force will now be equipped with body cameras. Potholes will be filled, snow will be plowed, grass in parks and on playing fields will be mowed and trees will get planted in the right-of-way. While our unemployment rate has fallen steadily over the past couple of years, our newly privatized program for economic development promises an even better job market in the future. We are going to help new businesses in their early stages and hope they will remain here once they become successful. We are going to aggressively seek to get established businesses to relocate here and we are going to fight to keep the great businesses of all sizes that already call Montgomery County home. Our avid readers and researchers will appreciate the interim Wheaton Library and extended hours at several branches. And students will have better access to after-school enrichment programs.

As Council President Floreen demonstrates above, this is not so much an Education First budget as it is an Everything First budget, with nearly every department and agency getting a piece of new tax revenues.

Let’s compare what happened this year to what occurred in 2010. Back then, the county was suffering from the full effects of the Great Recession. Its reserves were dwindling to zero, revenues were in freefall and its AAA bond rating was on the verge of being downgraded. The County Council responded by passing a budget with furloughs, layoffs, no raises for employees, a cut in the county’s earned income tax credit, an absolute reduction in spending and a $110 million increase in the energy tax. Given the dire economic emergency, all options were bad ones, but the council really had no choice. The cuts and tax hike were forced upon them.

This year, there is a stagnant economy (which we will discuss in Part Six) but no Great Recession. Reserves are substantial and have been on track to meet the county’s goal of ten percent of revenues. There is no threat to the bond rating. And yet, the council chose to pass a $140 million property tax increase – larger than the energy tax hike during the recession – when it could easily have reduced the tax increase, funded MCPS’s needs and not cut any other departments. But it did not.

Like all big choices, this one will have consequences. We will explore them in Part Six.

MoCo’s Giant Tax Hike, Part Four

By Adam Pagnucco.

The tax hike is the part of the budget that is getting the most attention, but the County Council took another unusual step: it refused to fund part of the county employees’ collective bargaining agreements. Labor has taken notice.

Salary increases in the county’s collective bargaining agreements are comprised of three main components. First, there is a general wage adjustment that all employees receive. Second, there is a service increment, also called a step increase, that employees who are not at the top of the salary scale for their classification receive. Third, there is a longevity increment that is received only by employees who are at the top of their scale and have completed twenty years of service. All of these items, along with many others, are negotiated by the three county employee unions (MCGEO, the Fire Fighters and the Police) and the Executive and codified in collective bargaining agreements. The agreements then go to the council, which can decide to fund all, some, or no items that create economic costs.

During the Great Recession, the employees received no raises of any kind in Fiscal Years 2011, 2012 and 2013. Afterwards, the unions negotiated for and received general wage adjustments, steps and longevity increments as well as “make-up steps.” The latter were intended to compensate the employees for steps they did not receive during the recession. The unions won make-up steps in Fiscal Years 2014, 2015 and 2017 (this year’s budget) with the exception of the Fire Fighters this year. During these years, the combined general wage adjustments, steps and make-up steps ranged from 6.8% to 9.8% per year.

This year, the council approved MCPS’s funding increase on the condition that some of the money scheduled to fund MCPS employees’ raises be instead redirected to hire teachers and other staff. The school board agreed. In order to maintain equity between MCPS employees and county employees, the council insisted that the county unions give up some of their raises and primarily targeted their make-up steps. The council refused to fund eight items in the collective bargaining agreements which together totaled $4.1 million in savings in Fiscal Year 2017, leaving the unions with raises of 4.5 percent. Only Council Member Marc Elrich voted with the unions.

The county unions were outraged. MCGEO, the largest of them, published a scathing response on its website, blasting the council as “hypocrites” who engage in “public manipulation in order to achieve what looks like sound fiscal management while achieving nothing.” The council had approved make-up steps and total salary increases of 6.8-9.8% in both 2014 and 2015, so what had changed now? The difference is that few people were paying attention in those two years because a tax hike was not on the table. Now that a large tax hike was being considered, big raises were not politically feasible. Hence MCGEO’s anger.

Justified or not, the council had achieved $4.1 million in savings by trimming employee salary increases. That money could have been used to reduce the property tax increase, but that’s not what happened. Why not? We will have more in Part Five.

MoCo’s Giant Tax Hike, Part Three

By Adam Pagnucco.

The need to fund MCPS was one reason given by county officials for their recent hike in property taxes. Another reason was the effects of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in the Comptroller of The Treasury of Maryland vs Wynne case. We examine that issue today.

The Wynne case started when two Howard County residents with income from a firm that did business in other states applied for an income tax credit to offset their out-of-state earnings. While they received a credit against their state income taxes, they were denied a credit against their county income taxes. The residents sued, and the case made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the court sided with the plaintiffs on a 5-4 vote. There were two consequences for local jurisdictions. First, they could no longer tax out-of-state income. Second, they owed refunds to residents who had paid taxes on out-of-state income dating back to 2006. Between the two changes, Montgomery County’s Department of Finance estimated lost county income tax revenue of $76.7 million in FY17 and FY18, $31.5 million in FY19, and $16.4 million annually after FY19.

When the Executive sent the council his recommended budget in March, then-current state law required that Montgomery County pay an estimated $115 million in refunds and interest in nine quarterly installments stretching into FY19. The hit in FY17 was $50.4 million. But Montgomery County State Senator Rich Madaleno, Vice Chair of the Senate’s Budget and Taxation Committee, passed a state bill that extended the refund payment period out to FY24. This reduced the county’s immediate liability and the Executive responded by asking the council to reduce his recommended property tax hike from 3.9 cents to 2.1 cents per $100 of assesable base.

Senator Madaleno’s legislation enabled the council to cut the Executive’s original $140 million tax hike by $33.7 million and still increase county funding for MCPS by $110 million. But the County Council did not take advantage of it. They increased property taxes by the Executive’s original amount anyway, a tax hike of 8.7 percent. Why did they do that? We will explore that question soon, but first we will examine another source of potential reductions in the tax hike: savings from collective bargaining agreements.

More in Part Four.

MoCo’s Giant Tax Hike, Part Two

By Adam Pagnucco.

The County Council is calling its recently passed budget an “Education First” budget since it included an increase above the state-required minimum level for Montgomery County Public Schools. Let’s evaluate that claim.

The council and the school system have had strained relations for a decade. The problems began under former Superintendent Jerry Weast, who antagonized several Council Members with his hard-charging, overdriven style. Nevertheless, Weast won several major budget increases for MCPS during his tenure. Then came the Great Recession, which forced the county to make substantial spending cuts across all of its agencies. One obstacle to cuts at MCPS was the state’s Maintenance of Effort (MOE) law, which sets a local jurisdiction’s per-pupil contribution to public schools as a base which cannot be lowered in future years unless a waiver is obtained from the state’s Board of Education. In Fiscal Years 2010, 2011 and 2012, the county cuts its per-pupil contribution to MCPS, and in 2012, it did so without applying for a waiver. As a result, the General Assembly changed the MOE law to force counties to apply for waivers or else have their income tax revenues sent directly to school systems. At the same time, the General Assembly shifted a portion of teacher pension funding responsibilities, once solely the province of the state, down to the counties. The combination of these two changes provoked outrage from county officials, some of whom vowed to never support a dime over MOE for MCPS in the future.

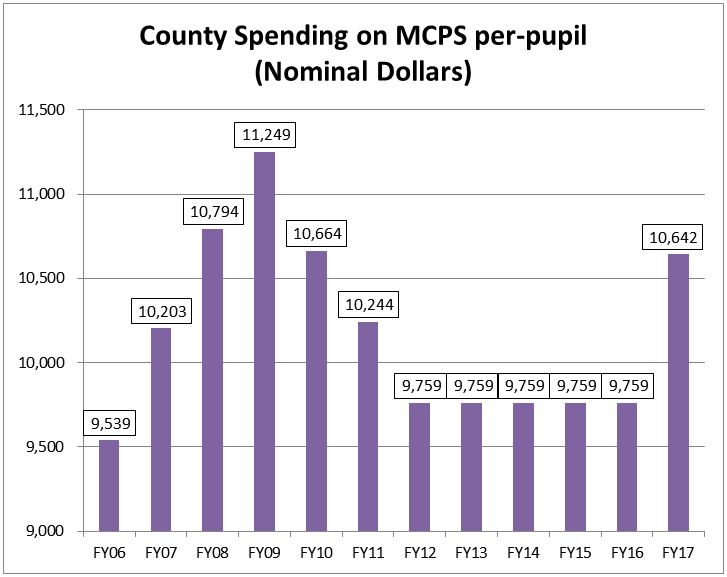

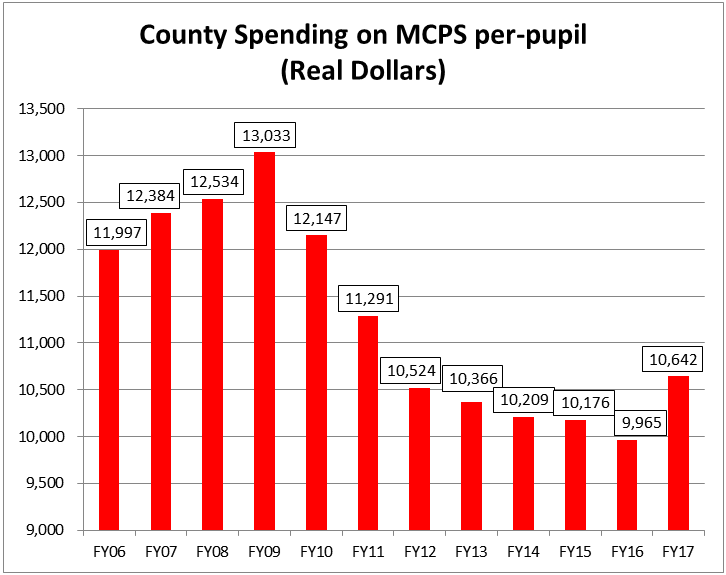

The chart below, which shows the recent history of Montgomery County’s local per-pupil contribution to the schools, illustrates the effects of these events. After rising through FY09, the per-pupil contribution fell for three straight years and then was frozen for four straight years. This year, the Executive proposed and the council approved an increased per-pupil contribution. (Roughly $300 of the increase is accounted for by the county’s payment of teacher pensions.) This is why the County Council is calling its budget an “Education First” budget.

But three items of context apply here.

First, the above chart does not include the effects of inflation, which erode dollar contributions over time. The chart below shows per-pupil contributions in real dollars using 2017 as a base. (Inflation in 2016 and 2017 is assumed to be 2.1%, the average of 2007-2015.) Adjusted for inflation, the county’s current per-pupil funding is nowhere close to what it was before the Great Recession struck.

Second, while MCPS was living under austerity, other county departments were receiving sizeable funding increases. The chart below compares funding increases across several county departments and agencies including MCPS between FY10 (the pre-recession peak year) and FY16. In terms of county dollars only, MCPS’s budget was cut from $1.57 billion to $1.54 billion over this period, a 2% cut, while many other departments enjoyed double-digit increases. Can one good year make up for seven years of austerity for the public schools?

Third, while county officials criticize the General Assembly for tightening the MOE law and shifting teacher pensions, it is the state that has been pumping substantial funding increases into MCPS’s operating budget. The chart below shows that while county funding for MCPS was cut by $33 million between FY10 and FY16, state aid to MCPS rose by $192 million.

The bottom line is that the new FY17 budget does add $110 million in local money to MCPS, an amount which exceeds the state-required maintenance of effort by $89 million. But this one funding increase comes after seven years of reduced and frozen per-pupil contributions, a period during which the rest of the government enjoyed double-digit increases. Council President Nancy Floreen has described the budget as “a historic partnership with the Board of Education” and “a plan for the future.” Does that mean that the council will continue to exceed maintenance of effort and give the school system increases that match the rest of the government in future years? Or will this be a one-year respite, after which austerity will return?

We will have more in Part Three.