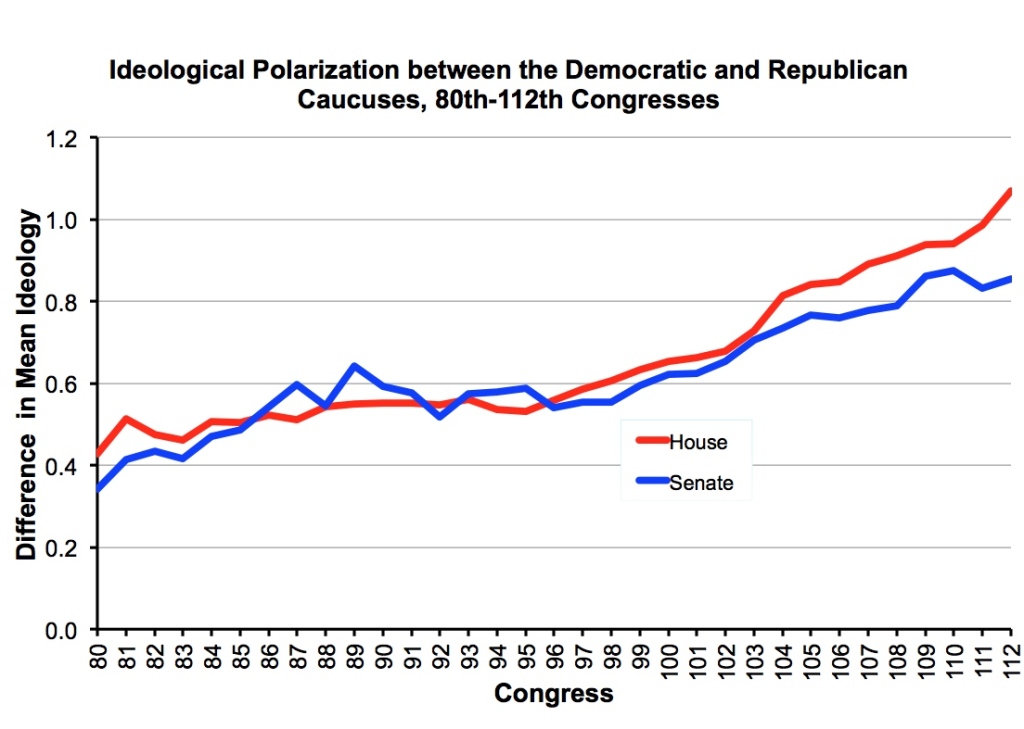

In the U.S., Democratic elected officials have become steadily more liberal while Republican elected officials have marched even faster in the conservative direction. As a result, polarization in the Senate and House of Representatives has increased:

The graphs show the difference in ideology between the average Democrat and average Republican over time–zero suggests no average difference in ideology according to the NOMINATE scores, which are widely used in political science. (UCSD Prof. Gary Jacobson, one of the country’s very top experts on Congress, kindly shared versions of these graphs with me.)

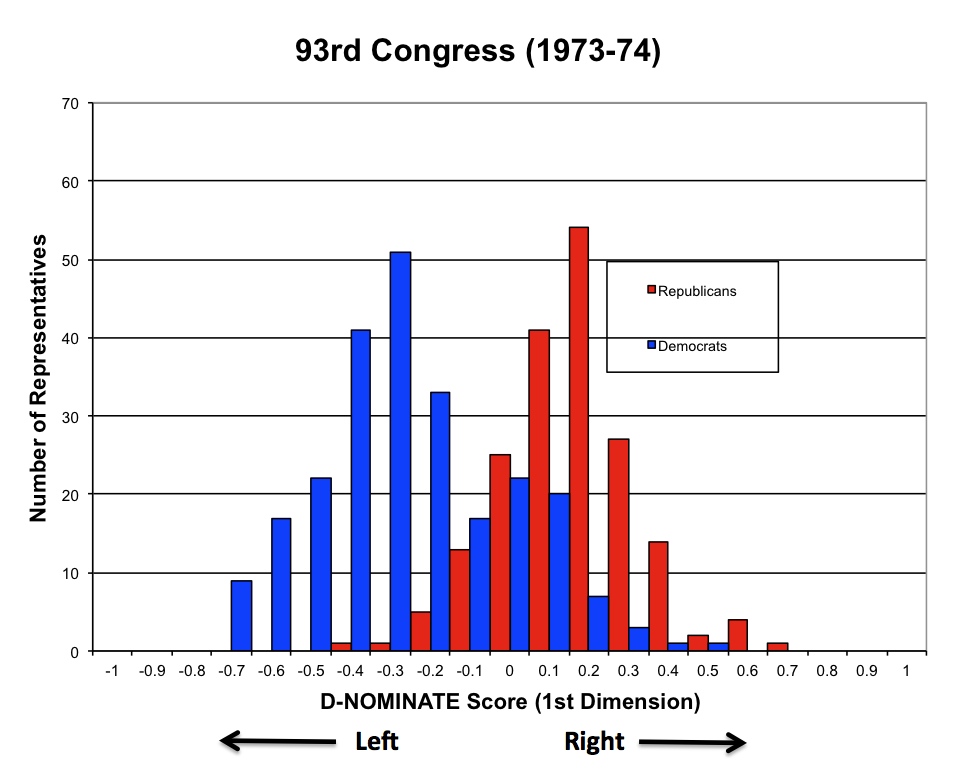

The increased polarization has resulted in the decimation of moderates in the House. Here is the distribution of representatives by party and ideology in the 93rd Congress:

According to the measure used here, right on the horizontal axis (i.e. more positive numbers) equates to greater conservatism while left on the same axis equates to liberalism (i.e. more negative numbers). Representatives with scores close to zero are relatively moderate.

In 1973-4, while Democrats tended to be more liberal than Republicans, there was still a lot of overlap between members of the two parties. A fair number of Republicans are more liberal than some Democrats. Similarly, many Democrats are more conservative than their Republican colleagues.

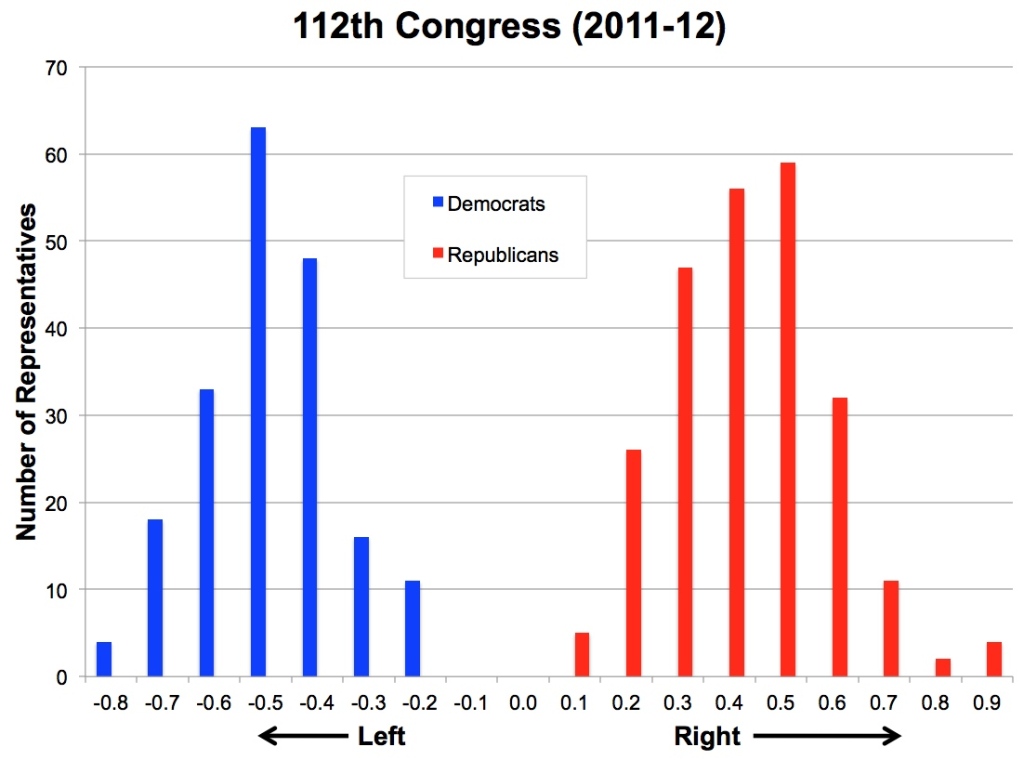

Now, look at the distribution for the House in 2011-12:

Not only is there no overlap between the two parties, there is even distance between the most liberal Republican and the most conservative Democrat. No wonder it is so hard to form bipartisan coalitions that can produce legislation in our divided government.

The new Congress will be even more polarized. The Democrats who lost tended to be among the most conservative members, such as Rep. Barrow from Georgia. Newly elected Republicans also tend to be more conservative than the colleagues that they replace.

Overall, both parties have become more extreme. The data indicates, however, that Republicans have moved twice as fast to the right as Democrats have to the left. But just because the Democrats have moved more slowly, does not mean that they will not eventually arrive.

Why is this happening?

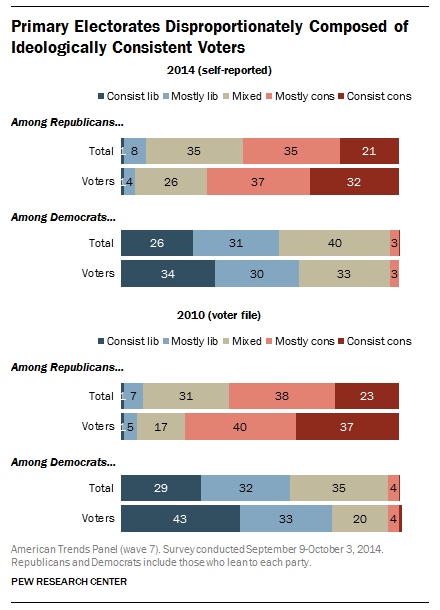

Many explanations are mooted to explain it but two factors have clearly played a major role: (1) the people who identify with each party are more ideologically homogenous, and (2) the people who vote in party primaries, and choose nominees, are more extreme than all members of their own party.

The following figure by Pew shows the composition of the primary electorates of both parties in 2010 and 2014. Among Democrats, 64% of primary voters were liberal in 2014 and 76% in 2010. Among Republicans, 69% of primary voters were conservative in 2014 and 77% in 2010.

The decline in extremism from 2010 to 2014 is illusory as the survey methods were different. Unlike in 2010, the 2014 survey utilizes self-reported voters but many survey respondents say they voted even though they did not and the non-voters are more likely to be moderates. Regardless, the primary electorates of both parties are more extreme than in past decades.

Most representatives are from districts that are generally safe for one party or the other, so they naturally focus on the party primary–heavily skewed in one ideological direction.

But even fewer safe districts wouldn’t really undercut polarization. The ideological distribution of primary voters is such that nominees must cater to them even if winning the general election requires moderation. Marylanders should remember when liberal Del. James Hattery beat more moderate Rep. Beverly Byron in the 1992 primary. Hattery then promptly lost the seat to Roscoe Bartlett.

The same dynamics are occurring in Maryland legislative elections. The new Democratic caucuses in the General Assembly will contain more liberal and fewer moderate members than in past years. The retirees and the defeated are disproportionately among the more conservative Democrats (e.g. Dyson and James). Similarly, the Republican caucuses will also be more staunchly conservative. Republican retirees (e.g. Kittleman and Brinkley) were more moderate and willing to work with Democrats than their replacements.

Governor-Elect Hogan is going to have a difficult time navigating these political waters. In order for legislation to pass the General Assembly, it will require substantial Democratic support. However, the required compromises risk alienating conservative legislators who are opposed to arriving at accommodations with the Assembly’s liberal majorities even though it is vital to the operation of Maryland government.

The next four years will be many things but boring isn’t one of them.