2012 Congressional District Map

2012 Congressional District Map

Redistricting remains one of the more contentious if arcane subjects in American politics. Unlike in many other western democracies with single-member district elections, such as Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom, the U.S. still usually allows politicians to draw both congressional and state legislative districts.

Some advocate that states ought to construct plans that are fair to Democrats and Republicans. And Maryland’s congressional plan has been attacked as unfair to Republicans not only by the GOP but by other observers, such as St. Mary’s College Professor Todd Eberly.

But how do you measure partisan fairness? Here are two basic principles that some see as underlining a fair plan that does not favor one party over the other along with an assessment of how well Maryland’s current plan lives up to them:

(1) No Partisan Bias. This principle is the simple idea that a party should win 50% of the seats if it wins 50% of the votes. Note that this is not the same as proportionality–that a party wins the same share of seats as votes.

There are different ways of testing for partisan bias. Examining the vote of statewide candidates in different districts is one simple way to test plans (not necessarily the best but easy to comprehend). The advantage of statewide candidates is that one can assess party performance with the same two candidates across all districts.

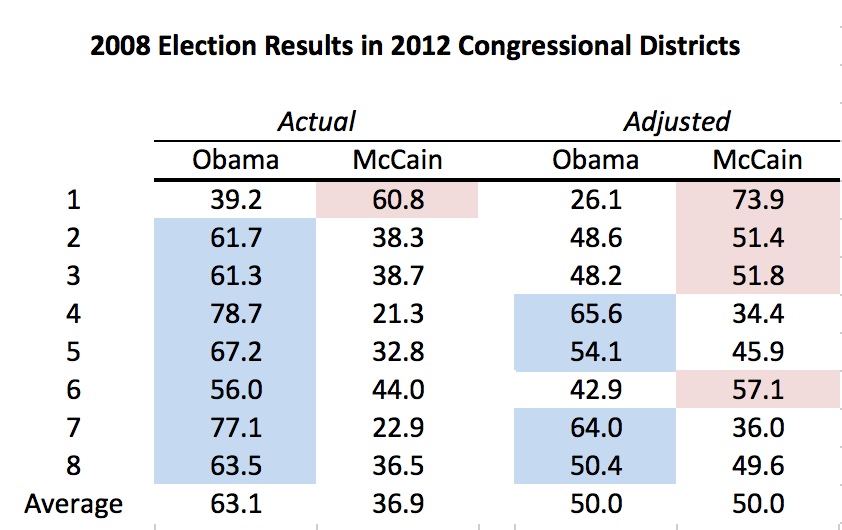

In this example, I use the presidential race. As is well known, Obama carried seven of the eight current districts in 2008. The two-party vote in each congressional district is shown in the first two columns:

Obama’s average vote share was 63.1%. But what if there was a uniform swing across all district of 13.1% towards McCain? Under this scenario, Obama and McCain would each have averaged 50.0% of the vote (see columns 3 and 4). Interestingly, each would also have carried four districts–exactly 50% of the total.

So the current plan passes a simple and cursory bias test. When each party receives 50% of the vote, each should win 4 districts.

(2) Symmetry reflects that if one party gains 65% of the seats with 55% of the votes, so should the other party. In single-member plurality elections, a party often gains a seat bonus when it wins more than a majority. This principle encapsulates the idea that such a bonus should be symmetrical and equal for both parties.

How symmetrical in Maryland’s plan? Again, examining the presidential vote is illuminating. In the example, below I envision a uniform swing across districts to estimate how many districts McCain would have won if he had received 63.1%–the share Obama actually won in the election.

The table suggests that McCain would have carried six districts–one less than Obama carried with the same share of the vote. So the plan is not perfectly symmetrical. The two black-majority districts (4 and 7) contain so many Democratic voters that even a Republican tsunami would not turn them blue, though the 7th comes close.

Examining the data in the table closely further suggests that Republicans would need only an additional 2.5% of the vote to carry all eight districts. However, Democrats would not achieve the same feat if they received the same vote share.

In truth, it can be very hard to construct plans free of bias and perfectly symmetrical. Moreover, swings are rarely uniform and the geographical concentration of partisans can shift over time. Of course, that also doesn’t mean we can’t often do better.

This at-first-glance examination also indicates that moaning about the partisan unfairness of the plan is not necessarily justified even though the plan was crafted by Democrats and one assumes designed to achieve their ends.

Complaints about the plan probably need to focus more on other issues. Next, I examine compactness–one of the major criticisms of Maryland’s redistricting plan.