By Adam Pagnucco.

Unfortunately for those Council Members who voted in its favor, last year’s 9% property tax hike won’t go away. The issue came up at the first County Executive forum, at which the three Council Members who voted for it defended it under heavy criticism from their Republican rival, Robin Ficker. It is sure to be mentioned again as several County Council candidates, including some Democrats, are openly wary of more tax hikes. And there is a general sense that the 40-point passage of term limits last year was driven at least partially by the tax increase. All local politicians have taken notice.

There is no question that the Giant Tax Hike is widely unpopular, but it cannot be undone, so let’s learn from it. Next year, the county will have a new Executive and at least four new Council Members. All candidates taking office will assume responsibility for a county with needs that have not abated and a budget that remains challenging. What lessons can these new office holders learn from the Giant Tax Hike? In this series, we present three of them.

Let’s start with Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS). Tax hike supporters point to MCPS’s needs as a reason for the increase and they have a point. MCPS has enormous and permanent needs. The school system is a huge asset that requires continuous large investments to maintain. But while all of that is true, the sad fact is that the county imposed seven years of austerity on MCPS while lavishing double-digit increases on nearly every other function of government. Once MCPS’s problems became too large to ignore, then and only then was the tax hike passed.

MCPS’s funding issues began when the Great Recession started impacting the county’s budget in 2009. The County Council has significant power to cut most parts of the budget but the school system is an exception. MCPS is covered by the state’s Maintenance of Effort (MOE) law, which establishes local per pupil contributions to school districts as a floor for funding levels in future years. The intent of the law is to prevent counties from supplanting state aid for schools by cutting their own local school funding and moving that money to other functions. Under the old MOE law, when a county wanted to cut its own local per pupil contribution, it needed a waiver from the State Board of Education or it would forfeit any increase in state aid for public schools. This penalty did not deter several counties from cutting local per pupil spending during the recession.

In Montgomery’s case, the county cut its per pupil contribution three times. In FY10, the county’s cut was forgiven by legislation passed in the General Assembly. In FY11, the county obtained a waiver for a cut from the State Board of Education, who warned the county not to cut again. In FY12, the county cut its local per pupil contribution for a third time without even asking for a waiver. Egged on by the teachers union, the General Assembly got fed up and changed the MOE law. From now on, if a county tries to cut its per pupil contribution without a waiver, the state would send the county’s income tax revenues directly to its school system to make it whole. There would be no more messing around with MOE.

This presented a budgetary challenge for counties. From now on, increases to local per pupil contributions would be almost locked in and very difficult to escape without the cooperation of local school boards. The new law was a risk factor that had to be managed. MoCo’s County Council reacted by freezing the county’s per pupil contribution for four straight years after three years of cuts. By FY16, the county’s per pupil contribution was $9,759 – well below the prior peak of $11,249 in FY09. Factoring in inflation, in real terms, the county’s per pupil investment in MCPS was 24% lower. That caused huge budgetary strain in the public schools.

The budget was only one reason for the county’s behavior. There was also politics. Over the years, former Superintendent Jerry Weast had constructed a machine combining the school unions, the PTAs and the Washington Post editorial board to aid him in obtaining budget increases. Increasingly, the council viewed him as going too far. That perception became more acute when he held a meeting with union leaders at his home in 2008 and directed them to endorse Nancy Navarro in the District 4 special election. Further strains appeared when Weast threatened to sue the county over MOE and the council accused the school board of lying about its budgetary needs in Weast’s last year. Weast’s successor, Josh Starr, was caught in the aftermath. He was unlucky enough to serve during MCPS’s austerity years and the budget squeeze effectively sabotaged his tenure.

While MCPS starved, the rest of the county government was well fed. Between FY10 and FY16, the county cut local funding for MCPS but increased it by double digits for most other government functions. The police department, the fire department, the libraries and almost every other department recovered nicely from the recession. The council itself enjoyed a 19% increase for its own operations. MCPS was almost alone in austerity. (Housing had a significant decline only because of a one-time large expenditure to the Housing Investment Fund in FY10). This profligacy throughout county government made it harder to afford an increase for MCPS without raising taxes later on.

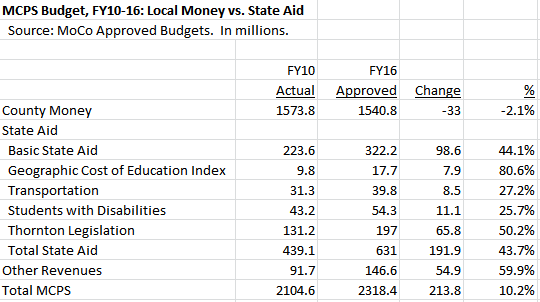

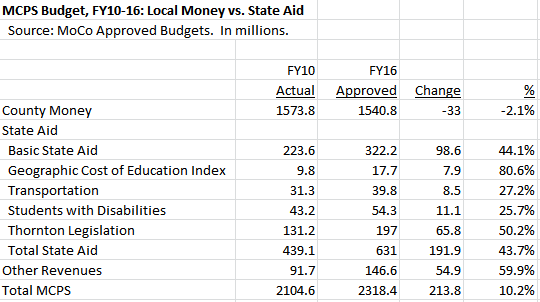

MCPS might have collapsed if it were not for state aid increases. Over the FY10-16 period, the county cut local operating funds for the schools by $33 million, but state operating aid went up by $192 million.

Meanwhile, many other counties reacted to the new MOE law differently. While MoCo froze its local per pupil contribution to its schools, fifteen other counties increased their contributions during the first three years of the new law. Nine of these counties were controlled by Republicans. That’s right, folks – supposedly progressive MoCo lagged Republican counties in increasing local support for schools.

After seven years of squeezing MCPS, the county finally relented and increased its per pupil contribution, but it did so with a 9% property tax increase. And it wasn’t just the schools that got more money – once again, nearly every other department got a bump. There’s a lesson here for the next generation of county leaders. MOE does indeed present a risk for the county budget, but it’s a risk that can and should be managed. Seven years of austerity for MCPS cannot be imposed without major strains on public school operations. A far better approach is to implement small but steady increases to per pupil funding while moderating growth in the rest of the government to pay for it. That’s the best way to maintain one of the county’s greatest assets without imposing giant tax hikes.

In Part Two, we will look at another lesson to be learned.