By Adam Pagnucco.

Part Two examined the case made by supporters of Bill 29-20, which offers 15-year property tax breaks on Metro development projects, and found that they have a point: namely, that the economics of high rises at Metro stations likely deter many such projects from being built. But there are other issues with the bill that should be addressed. Some of them are:

Smart growth was supposed to make money for the county.

There are plenty of good reasons to channel economic development through smart growth principles, including transportation management, community building, agricultural preservation, environmental considerations and more. But one of the cited reasons has historically been its alleged impact on county finances. Concentrating development in existing downtowns means that new road and sewer infrastructure does not need to be built. Nor do new police or fire stations. Schools may need to be expanded but new ones are not necessarily required as they may be by remote greenfield development. And high property values in downtowns can generate lots of property tax revenues that can be allocated across the county’s many needs. That was the plan at any rate. White Flint, one of the county’s earlier smart growth plans, was projected to generate $6-7 billion in revenue over the next 20-30 years back in 2010.

That was then. Now we are being told that if we want development at Metro stations, taxpayers need to pay for it.

There is no evidence that corporate payouts have paid off for MoCo overall.

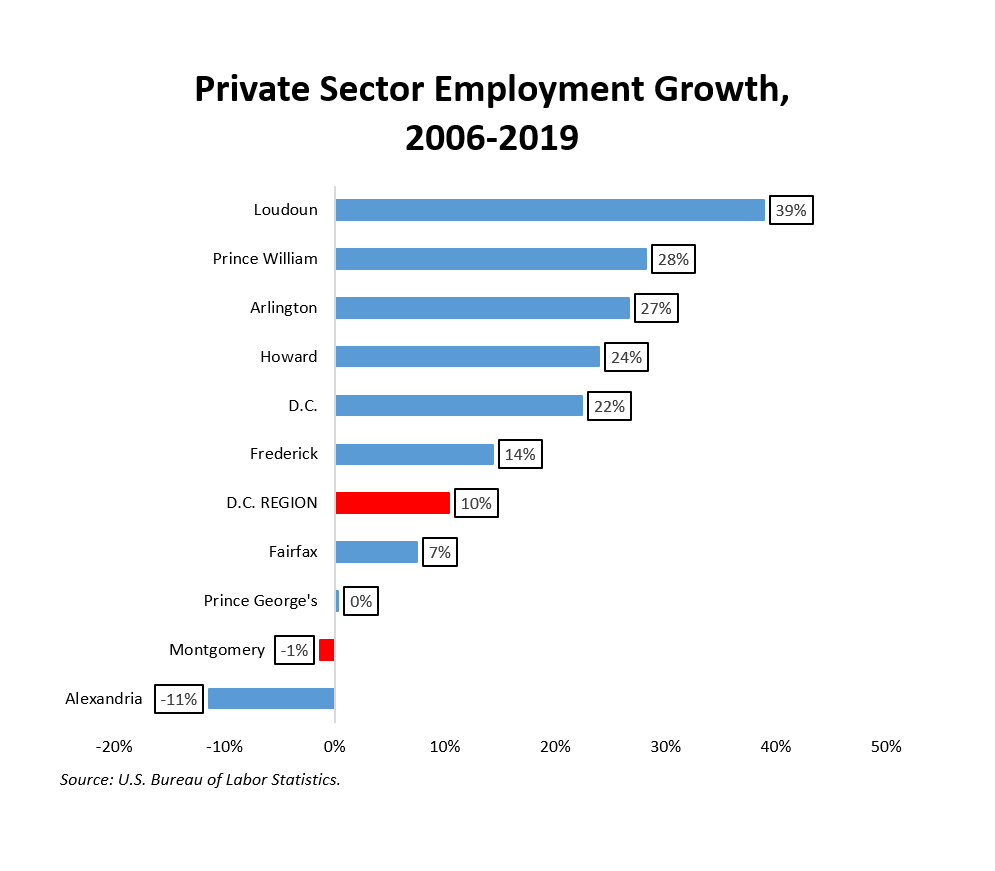

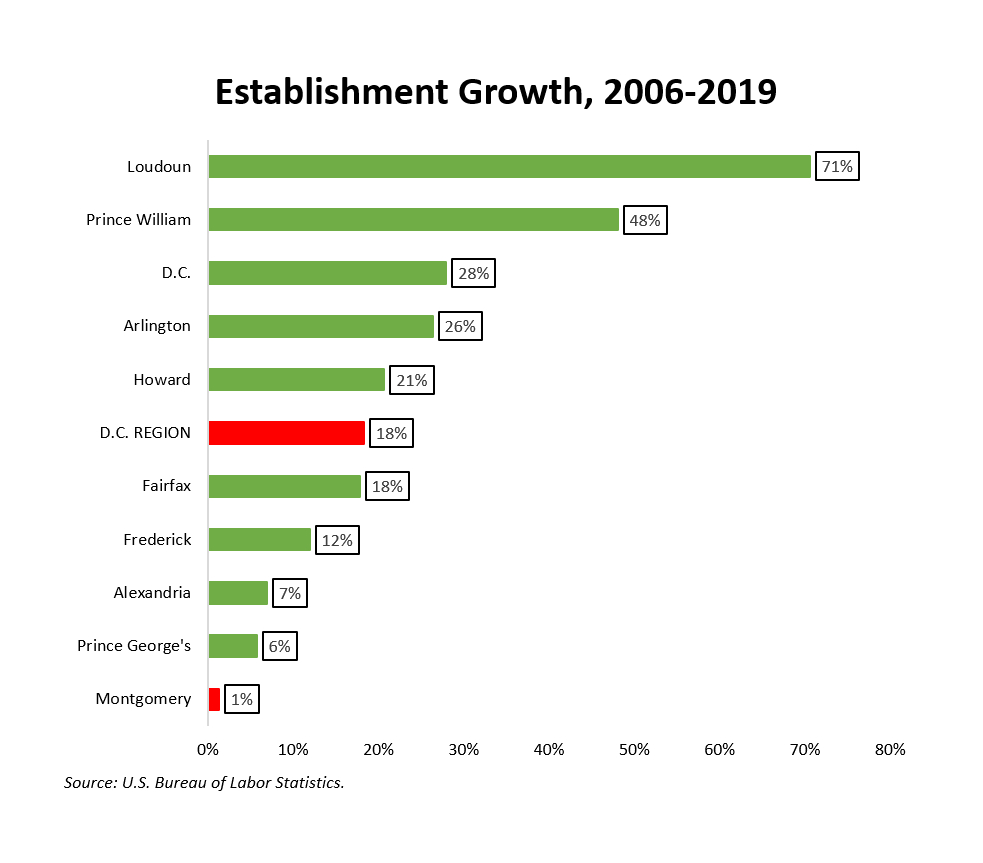

Bill 29-20 is far from the first corporate incentive proposal in county history. MoCo has handed out $67 million in incentives through its Economic Development Fund (EDF) over the last couple decades with millions more on the way. Most of this money has been expended for retention, not attraction. Four recipients alone – Fishers Lane (HHS), Meso Scale Diagnostics, Marriott and HMS Host – were allocated a combined $44 million in multi-year retention grants, of which $28 million remains to be paid. MoCo’s Democratic elected officials even gave a $500,000 subsidy to a subsidiary of Rupert Murdoch’s Fox Corporation. Despite all of these expenditures, the charts below shows how MoCo compares to its neighbors in employment growth and establishment growth since 2006, the county’s peak in the prior business cycle.

Here is the bottom line: we have been paying escalating amounts of corporate incentives for more than twenty years and it has not moved the needle on our economic competitiveness. Any time you do the same thing over and over and don’t get a positive result, you need to reconsider what you’re doing. Council members, think about it.

The county’s own actions make it a tough place for landlords.

Back in April, I wrote an article titled, “Why Would Anyone Want to Build Rental Units in MoCo?” summarizing the many deterrents to residential rental construction here. Among them were the time-consuming and expensive eviction process, the county’s moratorium policy (which does nothing to stop school crowding) and the election of a frequent development opponent as county executive. But little compares to the recent imposition of rent stabilization, which is supposed to be temporary but could always be extended. Many landlords were outraged at allegations of mass rent gouging when in fact there was little evidence to back that up. So are we now offering tax breaks in part to make up for all of this? Wouldn’t it be cheaper for taxpayers if the county simply stopped doing some or all of the above so that tax breaks aren’t necessary to get landlords to build units?

Property taxes by themselves are not the reason why MoCo can’t compete.

In waiving property taxes on Metro projects for 15 years, Bill 29-20 assumes that MoCo’s property taxes are a deterrent to development. But according to D.C.’s chief financial officer, MoCo’s effective property tax rate in 2018 was lower than in Prince George’s, Fairfax and Alexandria and not much higher than Arlington. And according to the General Assembly’s Department of Legislative Services, MoCo’s real property tax rate ranked 14th of 24 local jurisdictions in Maryland in FY20. On top of that, MoCo’s transportation impact taxes are far lower near Metro stations than they are in other parts of the county.

MoCo’s tax competitiveness challenge lies in its income tax (which is not charged by local governments in Virginia) and its energy tax. Bill 29-20 does not address either of those issues.

What are the consequences for income inequality?

High rises on top of Metro stations will be able to command some of the highest rents and/or condo prices in MoCo (and perhaps the entire region). In fact, such projects need to charge high rents and prices to pay off the costs of high rise construction and WMATA requirements. Bill 29-20 does not impose any additional affordable housing obligations beyond the 12.5-15% moderately-priced dwelling unit requirements in existing law. (Council Member Will Jawando introduced an amendment to raise the affordable housing requirement to 25% in committee but it was voted down.) So the bill in effect requires MoCo taxpayers to subsidize high-cost housing. Given the county’s long-standing problems with housing unaffordability and income inequality, that’s a hard pill to swallow.

And so Bill 29-20 presents a tough policy predicament. It’s true that high rise projects at Metro, the local Holy Grail for smart growth in the D.C. region, are not happening because of difficult project economics. It’s also true that sprawl and no growth are bad alternatives to transit-oriented development. But it’s frustrating that some of the architects and advocates of the county’s 15-year smart growth approach are now telling us it can’t happen without big tax breaks.

That said, corporate welfare can in rare cases be a necessary evil. If the county council wants to consider tax breaks for projects on a case by case basis, so be it. In doing so, the council can sort out projects that have a compelling public purpose from those that don’t. The council can also exercise leverage over a developer when public amenities like open space, child care, schools and other priorities are under consideration.

Bill 29-20 does not enable any of that. It creates an entitlement. Developers at Metro station properties will get tax breaks by right according to law. The council gives up most if not all of its leverage to influence such projects. And of course future developers might want to amend the law to get even longer tax breaks or other benefits. Developers of sites near but not on Metro stations might demand concessions too. As with the county’s Economic Development Fund, which began by handing out small grants to companies twenty years ago and eventually distributed 7-digit and 8-digit grants, the subsidies in the current bill may only be the beginning.

Metro station development was supposed to make us money. Now it seems we will have to pay for it, at least up front, to get the benefits that come later. Dear reader, this is your judgment to make. Is it worth it?